(5-6 Minute Read)

Genesis 32:4 – 36:43

In the Torah parasha, portion, of Vayishlach, Jacob sent messengers ahead to his brother, Esau, in the land of Edom. He told them to say, “To my lord Esau, your servant, Jacob, has stayed with Laban and acquired livestock and servants. I hope to gain your favor.”

The messengers returned to Jacob and informed him that Esau himself was coming to Jacob with a force of four hundred men. Jacob was greatly frightened; he divided his household into two camps so that if one was attacked, the other could escape.

Jacob prayed, declaring himself to be unworthy of the Almighty’s blessings but requesting that He deliver him from Esau’s hand. He also reminded the Most High of His promise to make his descendants too numerous to count.

Jacob planned to send his servants forward in waves with gifts of livestock for Esau in order to appease his brother.

That night Jacob sent his family and possessions over the Jabbok river. Being alone, a figure wrestled with Jacob until dawn, dislocating his hip. The figure demanded that Jacob release him, but Jacob refused until he received a blessing from him. The being replied, “Your name shall no longer be Jacob, but Israel.” The being refused to disclose his own name to Jacob, and Jacob named the place Penuel. Jacob developed a permanent limp from the encounter, and the descendants of Israel do not eat the sinew of the thigh to this day.

Seeing Esau approach, Jacob divided his children among his wives. He placed the two maids and their children first, followed by Leah and her children, and finally Rachel and Joseph in the rear. Jacob went forward and bowed low seven times and greeted his brother. Esau ran to greet him, embracing him and kissing his neck. Esau inquired about the women and children, and Jacob informed him that they were his family. Then they came forward to meet him. Esau then asked what the purpose was of the waves of servants and livestock gifts. Esau initially refused them, saying that he had plenty. But Jacob insisted, declaring that since the Most High had provided him with everything he needed. Esau was persuaded.

Esau suggested that they travel together to Seir in Edom. But Jacob insisted that Esau should go on ahead since they were required to travel slowly. Esau then wished to leave some of his men to escort, but Jacob politely refused this suggestion as well.

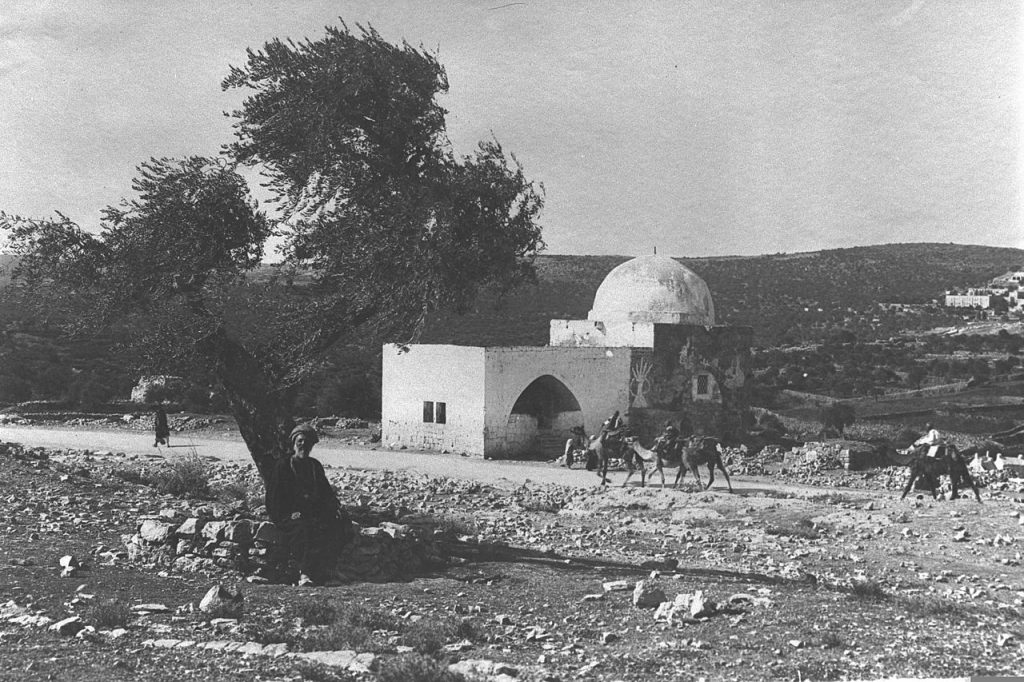

Jacob instead journeyed onward to Sukkot and made booths for his livestock there. He ultimately settled near the city of Shechem in the land of Canaan and built an altar there.

Dinah, Jacob’s daughter, went out to visit the daughters of the land. Shechem, the son of Hamor, the chief of the region, saw her. He took her by force and violated her. Being strongly drawn to Dinah, Shechem spoke kindly to her and requested that his father arrange his marriage to her.

Jacob heard that his daughter, Dinah, had been defiled. He remained silent until his sons returned home from watching the livestock. Jacob’s sons were distressed and outraged when they heard what had happened.

Hamor spoke to them and requested that his son be permitted to marry his son, Shechem, no matter the price. Similarly, he suggested that the family of Jacob intermarry and mingle with the people of the region and live there permanently.

Jacob’s sons replied deceptively that they agreed to Hamor’s request only on the condition that they all be circumcised. Hamor and his son agreed, and encouraged the men of the city to do the same, if only to acquire the wealth and livestock of Jacob’s family through intermarriage and other alliances. They all agreed and were immediately circumcised.

On the third day when the pain of recovery was greatest, Simeon and Levi, two of Jacob’s sons and Dinah’s full brothers, took up arms. They attacked the city and killed all the men by the sword. They killed both Hamor and Shechem and rescued Dinah; the other sons of Jacob plundered all the wealth and livestock of the town, and captured the wives and children of the men.

Jacob rebuked Simeon and Levi, complaining that the local inhabitants of Canaan would now loathe him. He feared they would band together to destroy him and his entire household. But they answered, “Should they treat our sister as a whore?”

The Almighty said to Jacob, “Arise, go up to Bethel, where I appeared to you when you first fled from Esau; build an altar there.”

Jacob told his household and all who were with him to rid themselves of their idols and change their clothing in preparation for their departure to Bethel. The complied, and Jacob buried their idols and jewelry under a large oak tree in Shechem. As they set out, the fear of the Most High overcame the nearby settlements; they did not harass or pursue the household of Jacob.

Devorah, Rebekah’s nurse, died and was buried under the oak below Bethel.

The Almighty appeared to Jacob after he arrived in Bethel and built an altar. He blessed him and said, “You shall be called Jacob no more, but Israel. A nation and kings shall descend from you, and I will assign them the land that I swore to Abraham.”

Jacob set up a stone as a pillar and poured oil on it as a libation and named the site Bethel.

The household of Jacob departed from Bethel. Before reaching Ephrath, Rachel entered difficult childbirth. As she died, she named her son “Ben-oni.” But Jacob instead called him “Benjamin.” Rachel was buried on the road to Ephrath near what later became Bethlehem. A pillar was set up at her grave, and Israel journeyed on.

At this time Reuben was intimate with Bilhah, his father’s concubine. Israel discovered the deed.

Jacob came to his father, Isaac, at Mamre, near Kiryat Arba and Hebron. Isaac died at the age of 180, and was buried there by Esau and Jacob.

One of the most important lessons that our rabbinical sages of blessed memory have taught from Vayishlach is the formula utilized by Jacob for mitigating and resolving conflict. When Jacob heard that Esau was en route to confront him with a force of four hundred men, he developed a response that could be described as: prayer, diplomacy, defense. First, Jacob prayed extensively, ultimately wrestling all night with a mysterious being. Second, Jacob sent waves of gifts to Esau in order to appease him. Finally, he divided his household into groups prepared to defend themselves, if it came down to it. Similarly, in our lives we can often apply this same formula to our own conflicts. First and foremost, we should always pray, beseeching the Eternal One for both protection and wisdom. Second, a diplomatic approach is often preferred, and can frequently minimize hostility. However, if diplomacy is ineffective, then we must take a stand to defend ourselves as necessary.

Relating to the diplomacy aspect of Jacob’s methodology, there might be another motivation for Jacob to bestow gifts of wealth on his brother. Esau was notoriously hedonistic; ostensibly Esau was only concerned about his stolen blessings in the context of financial loss. Jacob, however, realized that the real value of the blessings was primarily spiritual; the financial benefits were secondary. Thus, since the factor that enraged Esau was primarily a perceived economic loss, Jacob hoped to offset his rage by simply giving him wealth. Accordingly, Jacob probably suspected that if Esau did assault him, it would be for the purpose of stealing his wealth. In that sense, Jacob perhaps reasoned that if he gave his brother much of his wealth, then his wrath would be appeased and he wouldn’t bother attacking him. After all, why try to violently steal something from someone who is willing to give it to you?

Some have suggested that the text of the Torah may be alluding to the differences in approach by both Esau and Jacob. In regards to wealth, Esau states in Bereishit (Genesis) 33:9, “Yesh li rav, I have plenty.” But Jacob declared in 33:11 that since the Almighty had been so gracious to him, “Yesh li kol, I have everything [I need].” Accordingly, it has been noted by some that the difference between these two terms indicates the different philosophies of the twin brothers. Esau admitted that he had much, but implied that he wouldn’t mind having more, and made no mention of appreciation to the Eternal One for his blessed state. Jacob, however, first noted his gratitude for the blessings of the Most High, and then emphasized he had everything he could possibly need or want simply because the Almighty provided for him as was required. In other words, Esau’s response seemed to imply greed; Jacob’s reply indicated appreciation and contentment.

One of the most controversial accounts in the entire Torah (and Tanakh, for that matter), is the abduction and rape of Dinah. The great Sephardi chachamim, or rabbinical sages, known as Rambam and RambaN discuss at length whether Simeon and Levi were justified in destroying the entire town. The Rambam defends the action while the RambaN criticizes it, and this debate has been famously discussed at length throughout the centuries.

However, there is another question that can be asked about this story that often seems to be ignored. In Bereishit (Genesis) 34:5 (and elsewhere), the Torah text indicates that Jacob remained silent and did nothing when he first heard of the kidnapping and defilement of his only daughter. Never at any time did Jacob seem to express any real concern for Dinah or any real interest in recovering her. In fact, he didn’t even object when his sons, Dinah’s brothers, deceptively agreed to allowing Dinah’s rapist and kidnapper to marry her, essentially making the abduction and abuse a permanent status quo. Jacob’s only objection throughout the entire narrative was after the slaughter of the city of Shechem, and at that point Jacob complained of possible repercussions against himself from the locals. So the question is why did Jacob have seemingly no concern whatsoever about the welfare of his only daughter, and why did he even seem to be willing to abandon his daughter to her rapist permanently? Is this how a loving Jewish father would ever act? We can understand the murderous rage of Simeon, Levi, and her other brothers. But how do we explain the seemingly cold, heartless apathy of Jacob?

Some have suggested a possible answer, but it is not flattering for Jacob. One theory is that Jacob’s seeming coldness and possibly even animosity towards Dinah was an extension of the “battle of the wives” of Jacob’s household. Jacob had four wives (including Rachel and Leah’s maidservants) and twelve sons that perhaps could be categorized as “Team Leah” and “Team Rachel.” However, in addition to these wives and sons, Jacob had one daughter. For his entire life, Jacob had been very concerned with bloodlines and the affiliated blessings promised to him and his descendants from the Almighty, as his father and grandfather, Isaac and Abraham, had also been. Jacob, however, had taken this focus to another level, stealing blessings and birthrights from his brother. None of the other patriarchs had ever had a daughter; Dinah was the first. But how would that affect the balance of blessings? One midrash suggests that Dinah was to be married by Esau, but Jacob ardently resisted. While the veracity of this midrash is debatable, nevertheless it alludes to an idea that Jacob greatly feared the potential of his daughter as a possible pending matriarch outside of his own wives. Even worse, Dinah was the daughter of Leah, and therefore brought immense potential to “Team Leah” instead of “Team Rachel.”

With this theoretical context in mind, we might be able to understand why Jacob was seemingly unconcerned about his only daughter’s rape and abduction. Sadly, this theory indicates that Jacob might have considered the defilement and permanent kidnapping of the daughter of Leah to be highly convenient for him. He would no longer need to be concerned about such matters as another man marrying into his family and sharing his blessings with him, including Esau. Additionally, “Team Leah” would thereby lose the potency of their pending matriarch of the next generation, further enabling Jacob to make “Team Rachel” dominant despite their smaller numbers.

But could this really be? Is it possible that Jacob could really be so heartless and improperly obsessed with the distribution of blessings amongst his favorite family members that he would simply shrug off the kidnapping and rape of his only daughter? It is ultimately impossible to say, but some have pointed that there could be allusions to this idea in the text of the Torah itself.

First, it almost seems as though the Almighty Himself weighed in on the matter. Although there is a “chapter break” in modern versions, originally the Hebrew text was continuous. In that sense, immediately after Simeon and Levi declared in Bereishit (Genesis) 34:31, “Should our sister be treated like a whore?”, the Most High stated to Jacob, “Arise, go up to Bethel, and build an altar to the G-d who appeared to you as you fled from your brother, Esau.”

Some have postulated that these statements are actually connected in a form of unbroken dialogue. In other words, Jacob complained that his sons rescued Dinah with excessive (?) force; his sons decried the foul treatment of their sister; the Most High told Jacob to “Koom, alah, arise and go up” to Bethel where He first appeared to him. The Eternal One used two terms with Jacob for lifting himself up and elevating himself in the context of returning to Bethel. Some have suggested that the Almighty was actually responding to the situation by telling Jacob to “rise up” from this low, decrepit state. He commanded Jacob to “go up” both physically and spiritually to the place he was in when he first encountered the Most High in sincerity and humility. In other words, the Almighty instructed Jacob to “rise up” and “realign” himself spiritually with what was right and moral, just like he had been decades before.

Second, not long after this incident, Rachel died. After Rachel’s death, Reuben defiled Bilhah, Rachel’s maid, by incest. This action is clearly unusual, bizarre, and reprehensible; what could have possibly motivated Reuben to do such a thing? In light of the above perspective, Reuben, who was very loyal to his mother, was perhaps aggressively seeking to promote the status and interests of “Team Leah.” With Rachel dead and Bilhah defiled, now “Team Leah” would be dominant and receive the majority of love, affection, blessings, et al, from Jacob. And after Jacob had (theoretically) shrugged off Dinah’s own violation for the benefit of “Team Rachel,” Reuben now took revenge on his father by advancing the interests of “Team Leah” by incestuously defiling Bilhah, the only surviving matriarch within “Team Rachel.”

Third, later in the narrative of Jacob’s life we read the famous account of Joseph being sold into slavery and then ultimately becoming the viceroy of all Egypt. However, never at any time did Joseph even bother to send a message to his father about his condition, even when in great power, until his brothers had visited him several times unknowingly. Why didn’t Joseph contact his father, either to beg him to rescue him or to notify him of his position as viceroy later? In light of the above theory, it is possible that Joseph erroneously believed that his father, Jacob, had abandoned him just like he had deserted Dinah when she was kidnapped. After all, Joseph didn’t witness his father tearing his hair out in grief and saying, “We must rescue my poor daughter at all costs!” No; he saw his father remain coldly indifferent, completely silent, and totally inactive. Thus, following this theory, Jacob’s ignorance of Joseph’s fate could have been a natural consequence (and perhaps a Divine punishment) for his foul indifference to the terrible circumstances of his only daughter.

The study of the life of Jacob, especially as described in Vayishlach, has brought some to yet another question. Why do we glorify Jacob as such a hero, and why would the Almighty bless him as “Israel,” after whom the entire Jewish people have been named?

One possible answer relates to the fact that Jacob aligned himself with the Almighty’s true purpose for his life. Jacob committed himself to living his life in connection with the Most High and creating a family that would become the precursor of all future Jewish families. And that, in a sense, in many ways parallels the experience of the Jewish people at Mount Sinai. At Mount Sinai, the Jewish people all banded together and declared, “We will do and we will hear” all the words and commandments of the Almighty as outlined in the Torah. In other words, the Jewish people committed to aligning themselves with the Eternal One and embracing His formula for life, the Torah. But in the context of the Torah there are blessings and curses for obedience and disobedience respectively. Accordingly, we see all throughout the history of the Jewish people that we have been aligned with the Almighty and His purpose for our lives: Torah observance. And in that context we are blessed. However, we frequently don’t follow the Torah properly, and suffer the consequences thereof as well. In that sense, the Jewish people actually mirror the life of Jacob perhaps more than the other patriarchs. We are connected with the Most High and we have the Torah; but we are engaged in an incessant struggle to refine ourselves to live properly, and we frequently fail and suffer the consequences. And that is the very definition of Jacob’s life. However, just like Jacob, despite our shortcomings and failures along the way, we can ultimately prevail and be called “Israel,” a “prince with G-d.” And that is the very definition of “Israel” as the Jewish people as well the entire “Jewish experience.” Like Jacob, we are “Israel” not because we have no failures, but in spite of them.

May the Holy One, Blessed be He, ever grant us the ability to successfully overcome all adversity through the proper methodology. May we ever achieve stability and loving balance with each and every member of our families and communities. And may we all rise above our shortcomings and achieve the status of being a “prince” (or “princess”) with the Almighty, just as Jacob did when he became “Israel.”