(4-5 Minute Read)

Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11

The Torah portion of Vaetchanan begins with Moses pleading with the Almighty to allow him to cross over the Jordan River into the land of Israel. The Most High refused, but instead permitted Moses to ascend the mountain of Pisgah and observe the land from afar. The Holy One, Blessed Be He, then instructed Moses to appoint Joshua, the son of Nun, as his successor. Moses repeatedly implored the Jewish people to observe all of the laws and commandments of the Torah, never adding to or taking away from the Torah. The Jewish nation was reminded of our intimate encounter with the Almighty at Mount Sinai, and we are instructed to never worship any other god or goddess, or even any other version of the Most High, than what we experienced at Sinai. Moses especially reiterated firm prohibitions against any form of idolatry. Moses repeated the Ten Commandments and described the events surrounding the revelation at Mount Sinai. Following that, Moses then began his discourse that would later be incorporated into the famous Sh’ma prayer recited twice daily by the Jewish people. Moses concluded the parasha, or portion, by emphasizing that the Jews are never to coexist with the pagan Canaanites, avoiding intermarriage and rejecting idolatry.

The key theme of Vaetchanan is observance of the Torah. The Hebrew word shomer, or various grammatical variations thereof, meaning to “guard, protect, keep, or observe,” is found more than ten times in just three chapters. In this Torah portion, Moses’ intention is blatantly clear: he is insisting that the Jewish people, including all future generations, carefully keep and observe (shomer) the Torah.

Moses provided a variety of reasons and even “incentives,” if you will, as to why the Jewish people should observe the commandments of the Torah for perpetuity. One angle is that keeping the Torah results in blessings and the rejection of the Almighty’s commandments results in curses, including exile from the land of Israel. Another aspect mentioned is that we were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt. The Master of the Universe rescued us from oppressive, arduous slavery, and in exchange He gave us the “yoke” of the Torah. As the chachamim, or rabbinical sages of blessed memory, have discussed at length, in contrast to the bondage of Egypt, the “yoke” of Torah is actually the epitome of spiritual fulfilment and even liberty. Interestingly enough, however, never at any time does the Torah indicate that a Jewish person should observe the Torah for any considerations regarding the afterlife. Rather than concentrating on the realms after death, the Eternal One through Moses encouraged the Jewish people to observe the Torah in a manner that focuses exclusively on this life.

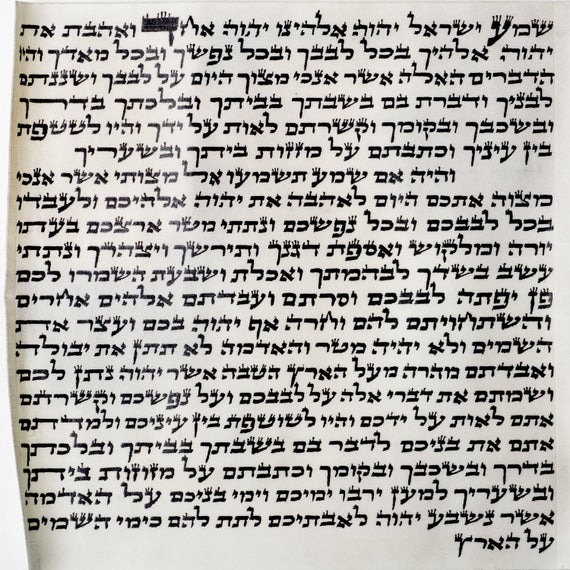

There is another approach that Moses emphasized that is perhaps the most important of all. Moses insisted that we are to obey the Torah because we love the Most High enthusiastically and wholeheartedly. The cornerstone of all Judaism is the Sh’ma prayer based on Devarim (Deuteronomy) 6:4-9 (and other Torah passages).

“Hear, O Israel, the L-RD is our G-d; the L-RD is One! And you shall love the L-RD your G-d with all of your heart and with all of your soul and with all of your might. Take to heart these instructions with which I charge you this day. Teach them to your children. Recite them when you stay at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you arise. Bind them as a sign on your hand and let them serve as a symbol on your forehead. Inscribe them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.”

One aspect of the Sh’ma that is perhaps a bit peculiar at first glance is the “command” to fervently love the Most High. In a similar vein, Vayikra (Leviticus) 19 tells us to “love our fellow person as ourselves.” What kind of “love” is induced by a strict command, even in the context of curses and punishments for the failure thereof? After all, imagine a person saying to their spouse, “Love me intensely, or you’ll be sorry!” Or imagine a political leader declaring, “You shall love me, or there might be legal consequences if you don’t!” Such rhetoric is wholly inappropriate, absurd, and even tyrannical. Perhaps more pertinently, such “love” is hardly sincere and therefore undesirable. So why does the Almighty “command” us to love Him and others?

Perhaps one perspective on this question is the fact that proper observance of the Torah is essentially impossible unless a person possesses two qualities: sincere love and reverence for the Almighty, and also a basic love and respect for our fellow human beings. In other words, maybe the inner purpose of the Sh’ma prayer is to serve as a daily declaration and reminder that the only way to truly, properly, and consistently keep all of the Torah commandments is by loving the Almighty, and not just by fearing the consequences of disobedience.

One possible analogy that can be used relates to the parent-child relationship. A child may obey his or her parent all throughout childhood for fear of punishment. But what happens when the parent is away and the child, now a teenager, is left at home for the weekend? If the chance of punishment is seemingly small, will the teenager still obey his or her parent? If the teenaged child loves and respects his or her parent, he or she will most likely follow the rules even in the absence of the parent. If not, then the teenager will probably do what he or she feels is best, following his or her own sense of wisdom or morality, or even worse, doing what he or she foolishly or selfishly desires despite the consequences.

Interestingly enough, immediately after the command to love the Almighty, Moses then reiterated the need of Jewish parents to teach their children to keep the Torah. Besides the fact that the only way to preserve Torah observance throughout the millennia is to consistently teach the next generation, could it be that even Moses himself had the parent-child model in mind when he described the mitzvah, or commandment, of loving the Most High?

The importance of loving the Almighty and loving others as being the central cornerstones of Judaism is reiterated in various ways by numerous great rabbis throughout our history, including Rabbi Hillel, Rashi, Rabbeinu Behaye, the Rambam, the RambaN, et al. Thus, one of the deepest messages of the Sh’ma prayer based largely on the text of Vaetchanan is that the only way to truly observe the Torah is to fervently love the Eternal One and to love others. Without first establishing a true love and respect for both the Most High and our fellow human beings, all efforts to follow the commandments of the Torah will inevitably fail. If we make our observance of the Torah an empty, rote ritual or merely going through the motions for the sake of avoiding punishment or any other reason, we are in danger of spiritually becoming like the “disenchanted teenager” of our previous analogy who will undoubtedly cease obeying his or her parent if he or she perceives an opportunity to do so.

In other words, the Almighty through Moses wasn’t being “emotionally tyrannical.” Rather, the Torah is our set of detailed guidelines on how best to connect and have a relationship not only with the Master of the Universe, but also with even the humblest member of our community. And since the entire Torah is based on love for the Eternal One and love for others, if we do not first possess that love, then Torah observance will be insincere and short-lived. Without love, Torah observance is essentially pointless and doomed to fail.

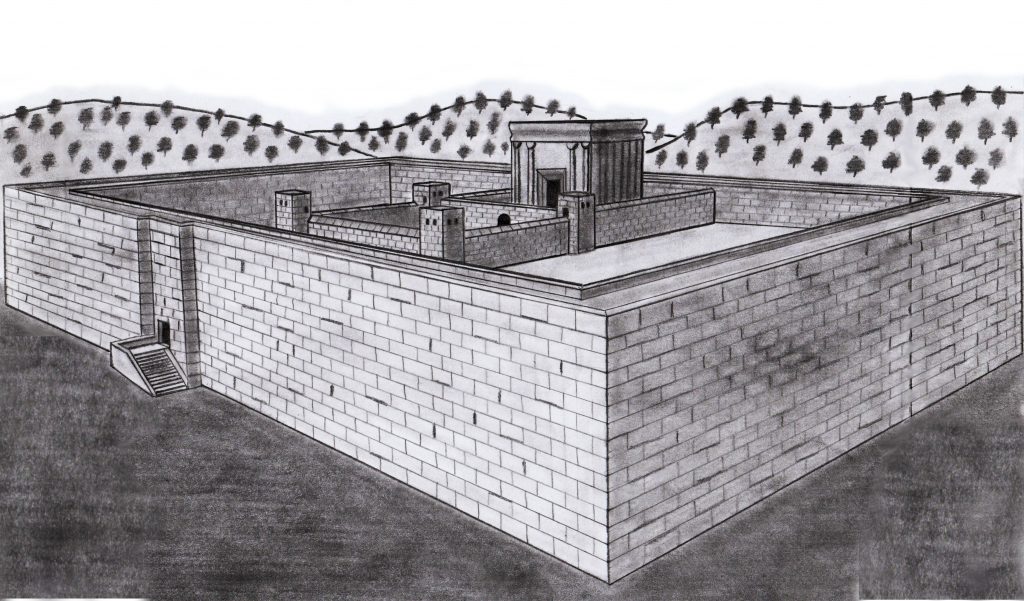

Following the Jewish calendar cycle, we have just concluded the season of Tisha B’Av commemorating the destruction of both Temples as well as numerous other calamities that have befallen the Jewish people. The chachamim tell us that the first Beit HaMikdash, or Temple, was destroyed due to idolatry and other similar sins. The second Beit HaMikdash was razed to the ground because of the sinat chinam, or baseless, freeflowing hatred, of the Jewish people for one another. In other words, in the days of the first Temple, the Jewish people had totally abandoned their love for the Almighty. In the second Temple period, the Jewish people had become completely devoid of love for one another, and instead embraced heinous hatred. In both cases, the Jewish people had reached a point in which having any kind of real or intimate connection with the Most High through the Beit HaMikdash, or Temple, had become essentially impossible. Therefore, the Master of the Universe allowed both Temples to be destroyed; at that time there was no purpose for their existence.

And perhaps that’s the true message of the Sh’ma prayer as well as much of the text of Vaetchanan. Without love for the Eternal One and our fellow humans, the Torah becomes meaningless for the observers, i.e. the Jewish people (has v’halilah). And when the Jewish people reach that state (again, has v’halilah), that is when Tisha B’Av calamities and other “curses” befall us. By separating ourselves from basic love, we push ourselves away from the Almighty and others. And such separation results in misery and “curses” for all involved.

May the Holy One, Blessed Be He, empower us to fill our lives with love not only towards Himself, but also for our fellow human beings. And may we bring this love into every aspect of our spiritual and communal relationships, observing the Torah at heightened levels and bringing the blessings thereof into our own lives, as well as those of our families and communities.