(3-4 Minute Read)

Numbers 13:1-15:41

Shelakh lekha is a Hebrew phrase meaning “Send for yourself,” and is the key theme of the parasha, or Torah portion, of the same name. The parasha begins with the Holy One, Blessed Be He, granting Moses permission to send twelve spies, one from each tribe, to scout out the land of Israel. Joshua and Caleb are included in this line up. After a forty day reconnaissance mission, the twelve spies returned to give their report. Ten of the spies admitted that the land of Israel was very fertile, but emphasized that it was full of strong enemies in fortified cities. As such, despite Joshua and Caleb’s insistence to the contrary, the ten spies declared that it would be impossible for them to conquer the land.

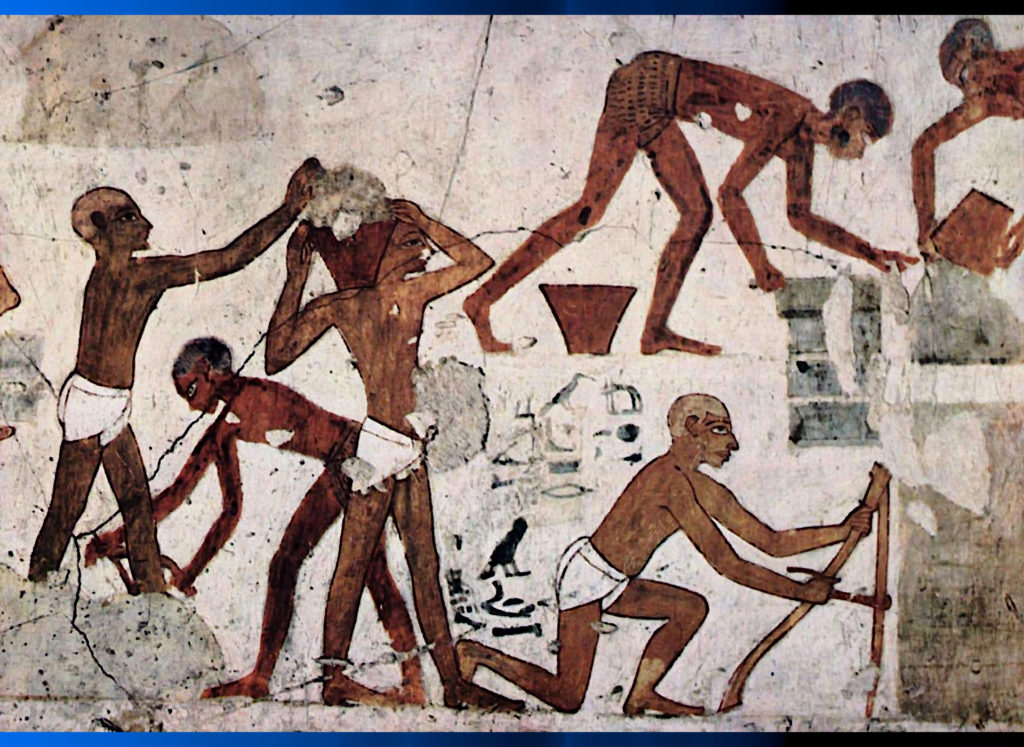

The Jewish people responded very poorly. They ultimately decided that they would rather be slaves in Egypt than enter the Promised Land, threatening to execute Moses and Aaron by stoning. The Almighty intervened, and even considered destroying the entire community of Israel. Moses pleaded for mercy on their behalf. The Most High agreed. However, He declared that the Israelites would wander in the desert for an additional forty years, and that none of the adult population would ever enter the land of Israel. Being grieved by this proclamation, some of the Israelites did try to invade the land the following day against the directives of the Eternal One and Moses. But they suffered an immediate defeat from their enemies.

Following these events, the Almighty resumed a discussion about sacrificial offerings. A man intentionally and rebelliously violated the regulations of Shabbat, or Sabbath, and was executed. And the Torah portion closes with the mandate of tzitzit, or religious fringes worn on the corners of our garments.

One of the questions our chachamim, or rabbinical sages of blessed memory, have asked is why the ten spies intentionally provided such a negative and damaging report of the land of Israel. Quoting the Zohar, some have stated that the ten spies were motivated by a preservation of their own power. From the time they left Egypt, key leaders of the twelve tribes had been placed into high levels of authority within the Israelite community leadership. And the more dependent the people of Israel were, the more power and influence the tribal leaders had. However, by bringing the Jewish people into the land of Israel where they could thrive independently, their reliance on the existing authority figures, ranging from tribal leaders to Moses himself, would dramatically diminish. And whereas Moses wanted the people to become more independent and self-sufficient, the ten spies and tribal leaders did not. So instead of helping lead the people of Israel into a state of Torah-based self-sufficiency, they wanted to keep the community in a status of weak and fearful dysfunction in order to maintain their position and control.

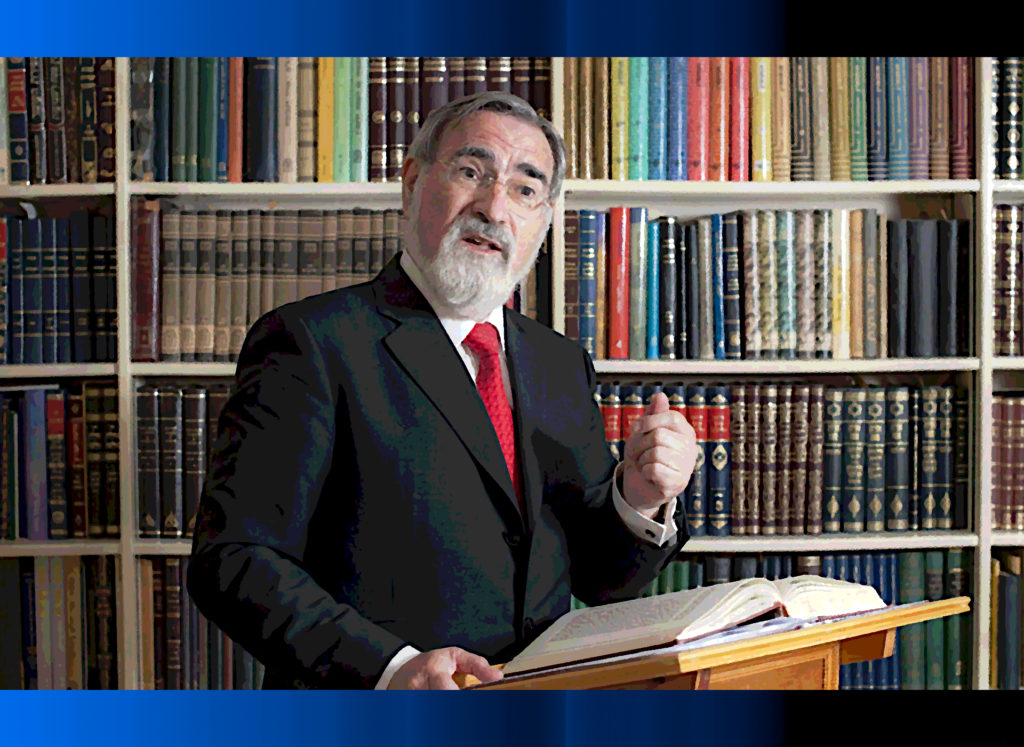

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks discussed this idea at length, citing the works of Professor Ronald Heifetz relating to leadership techniques. In a word, Professor Heifetz categorized leadership into several types, including technical leadership and adaptive leadership. Technical leadership is simpler, and involves a basic “do what I say” approach to a challenge or problem. For instance, a high-ranking officer giving an order to a bottom-level soldier is one example of technical leadership. The low-ranking soldier identifies a challenge, and the officer gives him or her clear instructions on how to overcome it. All the soldier needs to do is follow the orders given to him or her in order to achieve success. Adaptive leadership is more complicated. Adaptive leadership involves training an individual to develop his or her own solutions to a challenge. Adaptive leadership is not merely giving orders or instructions; it is teaching someone how to become his or her own leader.

The people of Israel had been enslaved for hundreds of years. As such, the only form of leadership that they were capable of functioning with was technical rather than adaptive. In other words, after serving Pharaohs and taskmasters for generations, the early Jewish people were unable or unwilling to operate in any other way. As Rabbi Sacks points out, the breakdown by Moses previously in B’Midbar (Numbers) chapter 11 is peculiar because the Israelites frequently complained about their menu of manna being the daily chef’s special. But why was Moses so grieved on this occasion, as opposed to previous instances of complaining?

Rabbi Sacks suggests that Moses was concerned because he could see that the Israelite people were rejecting the adaptive leadership principles that he had been trying to teach them. The Jewish people were at the border of the land of Israel. Rather than conducting themselves like strong individuals and a cohesive community, they instead were expressing themselves as slaves. Perhaps more than being concerned about their whining for more food variety, Moses was burdened by the fact that it had become painfully apparent to him that this nation of former slaves still thought, felt, and acted like slaves, rather than as a free and redeemed people.

In line with this thinking, Moses had a breakdown, despairing of the early Jewish nation. He especially noted that they were as incapable of self-sufficiency and responsibility as infants. Accordingly, the Almighty established a council of seventy leaders to assist Moses with the leadership tasks.

Bringing this same principle back to Shelakh Lekha, we can see what the Zohar and some rabbinical sages have expressed in regards to the events of the Torah portion. The people were weak and dependent. Some leaders, like Moses, actively sought to instill the principles of adaptive leadership, enabling the Jewish nation to function in a Torah-based yet independent way. But other leaders, such as the ten spies, desired to maintain a model of technical leadership that allowed them to rule as miniature dictators. And therefore they actively sabotaged the collective efforts to enter the land of Israel.

Similarly, we see the response of the people of Israel. According to the same premise, it seems as though the Jewish people themselves actually preferred the technical model rather than the adaptive model. When presented with the bad report, the Israelites despaired and also rejected the offsetting words of Joshua and Caleb. Instead, they decided that they should return to slavery in Egypt, and even considered executing Moses and Aaron. They were so incapable or unwilling to challenge themselves to become strong and independent in accordance with the directives and providential assistance of the Almighty, that they chose instead to return to the simple, technical leadership style of oppressive and even murderous Egyptian slavery.

The Holy One, Blessed Be He, responded by declaring that the entire generation of adults would wander in the desert for forty years, and it would be their children instead who would enter the Promised Land. Professor Heifetz also discusses the transition phase between technical and adaptive leadership. Besides being punishment for refusing to trust the Most High after witnessing countless acts of Divine assistance, it could be that the Almighty was indicating that it had become apparent that the adult generation of the people of Israel who departed from Egypt would never fully make the transition from technical to adaptive leadership. Accordingly, they would never succeed in functioning in the land, let alone conquering it from the Canaanites. In addition to the punishment factor, perhaps the Eternal One decreed that they would wander in the desert for the rest of their lives in a transitionary phase, since they couldn’t change their slave-type mentality and embrace the adaptive leadership that the Almighty and Moses tried to teach them. In contrast, their children who did not spend their lives in slavery would succeed in following a model more based on adaptive leadership.

Based on these ideas discussed by both the chachamim and Rabbi Sacks, one of the key takeaways of Shelakh Lekha is the acting philosophy of Torah-based Judaism. Some religions desire their followers to be robotic. They establish a hierarchy of technical leadership, in which the adherents follow their directives and religious texts blindly and without question. In contrast, Judaism is about adaptive leadership. It is about becoming responsible and self-sufficient in accordance with the directives of the Torah. Acting in a blind or robotic fashion is generally frowned upon. In fact, even the very nature of the Talmud and other rabbinical writings is that they are a collection of discussions and even debates among our spiritual leaders as to the best way to observe the Torah. The Almighty doesn’t want us to follow the Torah from a place of weakness, since that will ultimately lead to failure. Rather, the Most High calls us to become strong in our Torah-based leadership of ourselves, our families, and our communities.

May the Holy One, Blessed Be He, enable us to reach our highest potential. And may we express more and more leadership in our own lives in accordance with Torah directives, bringing our families and communities together in unity and an increased connection with the Eternal One.