(6-7 Minute Read)

It was a cool, brisk morning in November of 2018. Or, at least, it was cool and brisk by the standards of the residents of the Jerusalem, the capital of Israel. About thirty Jewish men had gathered together in the Kehilat Bnei Torah building in the Har Nof neighborhood of Jerusalem, a structure that housed both a synagogue and a yeshiva. The worshipers were mostly Orthodox or Haredi, their black suit jackets and brimmed black hats had been pushed backward or set off to the side to accommodate the tefillin and tallitot, or phylactery prayer boxes and fringed prayer shawls worn during morning prayer, or shacharit.

Among these thirty prayer service attendees were five rabbis in particular. The first rabbi to be noted was Rabbi Moshe Twersky. He was the grandson of the famed Rabbi Josef B. Soloveitchik, and the son of the founder of Harvard’s Center for Jewish Studies. He immigrated to Israel from Boston with his family, and eventually came to be the head of Torat Moshe Yeshiva, while his wife ran the Hadar Seminary for Women in Jerusalem.

Rabbi Kalman Levine had been born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri. After studying in a yeshiva in Los Angeles, he ultimately moved to Israel in the early 1980’s. Rabbi Levine could always be found praying in the synagogue or studying with an ever-present sefer, or holy book, tucked underneath his arm.

Rabbi Avraham Goldberg was a British Jew from Liverpool and London before immigrating to Israel in 1991. He was a “pillar of the community,” and provided for himself and his family through the development of computer programs and serving as an advisor for Haredi Jews entering the workforce.

Rabbi Aryeh Kupinsky was originally from the Detroit area, but relocated to Israel with his family when he was eleven years old. Besides also being a yeshiva scholar, he similarly worked with computers like Rabbi Goldberg. Rabbi Kupinsky also served in the Casualty Identification Unit of the Israel Defense Force Rabbinate, and functioned as a supervisor of kashrut, or kosher food.

Rabbi Haim Rothman was a native of Toronto, Canada, before moving to Israel in 1985. Rabbi Rothman worked for the State Comptroller, and often bracketed his day in the office with time in the synagogue, praying in the morning and studying in the evenings.

These five men had a lot in common. They were all originally from an English-speaking foreign nation, namely the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. All of them supported their local community in key functions. Some of them had even followed a similar career path. But most importantly of all, all five of them were Torah-observant Jews strongly connected to their faith and heritage as well as their connection with the Holy One, Blessed Be He.

Accordingly, these five rabbis had risen early that morning and made their way to the local synagogue along with about thirty other worshipers for prayer, as did countless other Jews all across the land of Israel and beyond. They rolled up their sleeves and momentarily set aside their brimmed hats to wrap their tefillin around their arms and set their tefillin on their heads in conjunction with their dark yarmulkes. The chazzan, or prayer service leader, chanted through the liturgy of the shacharit morning prayer service. Soon the thirty Jewish men praying together in the synagogue had clutched their tzitzit fringes in one hand while covering their eyes with the other, declaring the unity and “One-ness” of the Most High, while repeating the key Torah creed that we are to love the Almighty with all of our hearts, souls, and might. Following the Sh’ma prayer, the five rabbis and other Jewish worshipers stood in silent meditative prayer, reciting the Amidah and blessing the Most High in a series of benedictions.

Two men burst into the synagogue. Uday Abu Jamal and Ghassan Abu Jamal were Palestinian Arab cousins who worked at a nearby grocery store. They were armed with an axe and a meat cleaver. Brimming with unquenchable hatred, they charged into the holy sanctuary of prayer. They stabbed and hacked as many Jewish men as they could in the middle of their serene morning worship. Hebrew blessings of prayer were now replaced with Arabic shouts of “Allah u-akbar!” The Jewish worshipers attempted to fight back, especially Rabbi Haim Rothman who hurled any object he could find at the two Palestinian Arab terrorists. Another Jewish man heaved a chair at the assailants before escaping the carnage. Blood splattered on the siddurim, or prayer books, and desecrated the white walls that had echoed with Hebrew words of prayer just moments before.

Within minutes four of these aforementioned Jewish men, Rabbis Twersky, Levine, Goldberg, and Kupinsky, had all crumpled to floor or elsewhere, dead or dying. Rabbi Haim Rothman, who had put up a particularly fierce resistance to the attack, had suffered numerous blows to his head and body from the terrorist’s meat cleaver, and was critically wounded. After being in a medically-induced coma for nearly a year, eventually Rabbi Rothman died as well.

Almost immediately after the commencement of the attack, two Israeli police officers arrived on the scene. Although normally tasked with traffic enforcement, the Israeli policemen rapidly approached the synagogue in an attempt to thwart the violent attack.

In addition to axes and meat cleavers, one of the two Palestinian Arab terrorists was also armed with a handgun. A gunfight ensued. Bullets from both the Israeli law enforcement officers as well as the terrorists added to the chaos and bloodshed of the attack. More Israeli police officers arrived at the scene to reinforce the first two. Finally, the Israeli policemen had shot and killed both terrorists, ending the carnage. But not before the first responding police officer, Master Sergeant Zidan Saif, was shot in the head. Critically injured, he soon succumbed to his wounds and died.

The attack on the Har Nof synagogue in November of 2014 was not the only heinous terrorist attack that Palestinian Arabs have perpetrated in Jerusalem. But it was unique in several categories. First, it defied the “stereotypical motive” for Palestinian Arab terror. Palestinian Arab organizations routinely cite political “excuses” for their support of violence and terrorism. The Palestinian Arab narrative is littered with dubious claims of ostensibly stolen land, supposed “settler” mischief, and alleged cruelty by Israel Defense Force soldiers. Accordingly, many victims of terrorism have been Jews living in Yehudah v’ Shomron, or Judea and Samaria, as well as IDF soldiers.

In contrast, the victims of the Har Nof synagogue attack were not soldiers or “settlers.” Rather, they were Orthodox and Haredi Jews focused on their own lives in western Jerusalem, an area that is not disputed by anyone as supposedly belonging to the Palestinian Arabs, as opposed to “east Jerusalem,” for example. In this regard there was no clear political “excuse” for the attack.

Uday Abu Jamal and Ghassan Abu Jamal were related to a convicted operative of the terrorist organization, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, or PFLP. They had indicated that their motivation for the attack was connected to the erroneous belief that the suicide of an Arab bus driver had actually been a murder perpetrated by Israeli Jewish “settlers.” They also decried a perceived threat of Israeli authority allegedly encroaching against the Al Aqsa mosque on Har HaBeit, or the Temple Mount.

Uday and Ghassan worked at a grocery store in the Har Nof neighborhood of Jerusalem near Kehillat Bnei Torah. Every day they watched Torah-observant Jewish persons file in and out of the synagogue and yeshiva, glaring at them with lethal hatred. Uday and Ghassan longed to kill as many of them as they could, not because they were Israeli soldiers who had supposedly engaged in underhanded acts of barbaric violence against their fellow Arabs, not because they were part of an Israeli “settler” community ostensibly expanding into their perceived territory, but for one simple reason only: these five rabbis and the other worshipers of Kehilat Bnei Torah were proud Jews, openly displaying their heritage and clearly brandishing their status as being very traditional and stringent in their practice of Judaism

The terrorism perpetrated by Palestinian Arab organizations is often portrayed as being “limited” only to those entities or persons who supposedly “deserve it,” such as “brutal soldiers” and “colonizing settlers.” But the attack on the Har Nof synagogue and yeshiva that ultimately left five rabbis from America, Canada, and the United Kingdom viciously murdered and several other victims terribly wounded is one of the evidences that the motivation for Palestinian Arab violence is unlimited hatred of all Jews.

There is another aspect that makes the Har Nof attack unique. Besides the five rabbis, another man gave his life as al kiddush Hashem, or an act of holiness. He wasn’t a rabbi or a Torah scholar. In fact, he wasn’t even Jewish. He was an Arab. Master Sergeant Zidan Saif was both an Israeli police officer as well as an Arab of the Druze faith. He had no direct connection to the Jewish people; he had no personal interest in whether or not the rabbis and other Jews inside the synagogue lived or died. He charged into the synagogue in an attempt to end the terroristic violence out of dedication to a people that were not his own, out of duty to a nation of which he was a small minority, and out of righteous fury against vile perpetrators of heinous evil.

The thirty year-old Druze Arab police officer left behind a wife and a baby daughter only seven months old. Thousands attended his funeral in the village of Yanuh in the Galil region of northern Israel, including Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, National Police Commissioner Yochanan Danino, and Public Security Minister Yitzhak Aharonovitch. The latter eulogized Zidan Saif, saying:

“We are burying a hero of the Israeli police, who laid down his own life to protect the worshipers of at the synagogue of Har Nof… [Zidan Saif was] a courageous warrior. His heroism cost him his life, but saved the lives of others.”

The leaders of the Druze Arab community similarly spoke words of eulogy for the fallen Israeli police officer. Druze Sheik Moafaq Tarif also mentioned another Druze Arab who had died in the service of the Jewish state as a Border Policeman, Jidan Assad. Jidan had been killed in the line of duty by a Palestinian Arab terrorist just a few weeks prior.

The Orthodox and Haredi Jewish communities also expressed their support and appreciation for Master Sergeant Zidan Saif. Former Chief Sephardi Rabbi of Israel, Rav Ovadia Yosef Z”L (of blessed memory) issued a halachic ruling, stating:

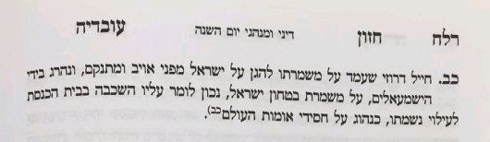

“A Druze soldier on duty who defended Israel against its enemy… and was killed at the hands of the [Arabs], for the sake of guarding the security of Israel, it is correct to recite for him a hashkava, a memorial prayer for the deceased, in the synagogue for his soul…”

Similarly, a Haredi Jewish student and activist, Risha Segal, announced:

“We are calling for widespread solidarity throughout Israel, with an emphasis on gratitude… We will show our thanks for those who sacrificed their lives for us. This is one of the most important principles in Judaism… Terror does not distinguish between religions and nationalities, it kills innocent people indiscriminately.”

Along the same vein, a story is told about Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach Z”L. Rav Auerbach, the head of Kol Torah, a large Haredi yeshiva, was approached by one of his students about taking time off from his studies to visit the graves of the tzaddikim, or the righteous giants, in Zfat and other areas of the Galil in northern Israel. Rav Shlomo Auerbach responded:

“In order to pray at the graves of tzaddikim, one doesn’t have to travel up to the Galil. Whenever I feel the need to pray at the graves of tzaddikim, I go to Mount Herzl [the national cemetery for fallen IDF soldiers in Jerusalem] to the graves of the soldiers, who fell al kiddush Hashem, in an act of great holiness.”

The Israeli political spectrum has been plagued with much discussion and debate about Orthodox and Haredi Jewish interaction and inclusion in broader Israeli society. These political issues are complex and a topic to be discussed at another time. Meanwhile, on this Yom HaZikaron, or Israeli Memorial Day, perhaps we can all unite and focus on the great sacrifice al kiddush Hashem made by many men and women of the Israel Defense Force who gave their lives to protect others. And perhaps also we can be reminded, as Rav Auerbach Z”L pointed out, that tzaddikim, or righteous giants, can sometimes turn out to be someone unexpected, even a Druze Arab defender of the Jewish people.