(5 – 6 Minute Read)

Exodus 27:20 – 30:10

As the narrative continues about Tabernacle construction and service in Tetzaveh, the Almighty further commanded Moses to instruct the Israelites to bring clear olive oil for lighting the lamps set up inside the Tabernacle. Aaron and his sons would light them regularly to burn perpetually from evening to morning for all time and throughout the ages.

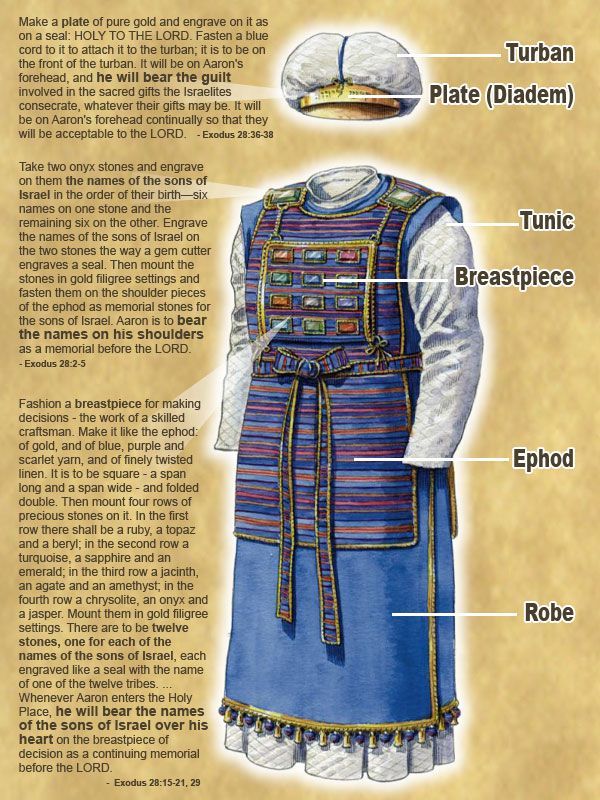

Aaron and his four sons, Nadab, Abihu, Eleazar, and Ithamar, were to serve the Almighty as priests. Moses was to have sacral vestments made for them by skillful artisans, including a breastpiece, an ephod, a robe, a fringed tunic, a headdress, and a sash.

The ephod would be made of these colored materials of gold, blue, purple, and crimson, and have two attached shoulder pieces. Two lapis lazuli gemstones would have the names of the sons (i.e. tribes) of Israel engraved on them — six to a stone — in order of their birth. They would be framed in gold and attached to the ephod as a remembrance of the Israelite people before the Eternal One.

The breastplate of judgment (i.e. decision) would be rectangular in shape and also be made from the colored materials. It would house four rows of three stones, all of various gemstones framed in gold mountings corresponding to the twelve tribes of Israel. The breastplate would be outfitted with gold rings and chains in order to support it from the shoulder pieces of the ephod, and also held in place on the ephod by a blue cord. The Urim and Thummim* [decision-making oracle] would be placed inside of the breastplate. Thus, Aaron would carry the names of the sons (i.e. tribes) of Israel on the breastplate and Urim and Thummim over his heart when he entered the [Tabernacle] sanctuary (and all other times) as a remembrance before the Most High.

The robe of the ephod would be made of pure blue, with a woven work around the head opening. On the hem of the robe they were to make pomegranates of colored yarns along with bells of gold. Aaron would wear the robe during his official service, so that the sound of it would be heard in the [Tabernacle] sanctuary and he would not die.

A headdress of fine linen was to be made with a golden frontlet suspended by a blue cord and bearing the engraved inscription, “Holy to the Almighty.” It would be on Aaron’s forehead at all times, so that he could remove any sin arising from the holy things donated and consecrated by the Israelites.

They were to make a fringed tunic of fine linen and an embroidered sash along with linen breeches to ensure modesty for both Aaron and his sons. This was to be a law for all time for Aaron and his descendants to come.

In order to consecrate the priests, the Almighty instructed Moses to collect a young bull and two rams along with unleavened bread and cakes mingled with fine oil placed in a basket. At the entrance of the Tabernacle Aaron and his sons would be washed with water, clothed with the sacral vestments*, and anointed with oil. The priesthood would thus belong to them for all time.

Moses would ordain Aaron and his sons as they placed their hands on the bull. It would be slaughtered before the Most High at the entrance of the Tabernacle. Some of the blood would be put on the corners (i.e. horns) of the altar, the fat and some internal organs would be burned on the altar, and the rest of the bull would be burned outside the camp for a sin offering.

Next, a ram would be slaughtered after Aaron and his sons laid their hands on its head. Some of its blood would be dashed upon the sides of the altar. The ram would be cut up into sections and burned on the altar.

Aaron and his sons would lay their hands on the other ram and slaughter it. Some of the blood would be placed on their right ears, right thumbs, and right big toes. The remaining blood would be dashed on the sides of the altar. Some of the blood from the altar and some of the anointing oil would be sprinkled on Aaron and his sons as well as their sacral vestments. Thus Aaron, his sons, and the vestments would be holy.

Some of the fat of the ram as well as its right thigh along with some of the unleavened bread and oil cakes would be placed in the hands of Aaron and his sons as an elevation offering to the Almighty. Moses would take them from their hands and burn the offering on the altar.

The breast of the ram was to be offered as Moses’ portion. These breast and thigh parts would be due for all time from the Israelites to Aaron and his descendants as sacrifices of well-being.

The sacral vestments would pass on from Aaron and his sons to their descendants. Aaron or his successor would wear the vestments for seven days.

The meat of the ram would be boiled and eaten by Aaron and his sons along with the unleavened bread and oil cakes at the entrance of the Tabernacle, and not by a layman; they would be holy. Thus Moses was commanded to do to Aaron and his sons in a seven day process that would also purify and consecrate the altar.

Each day two year-old lambs would be offered on the altar — one in the morning and one in the evening — along with a specification of choice flour, fine oil, and wine. It would be a consistent burnt offering at the entrance of the Tabernacle throughout the generations.

The Almighty declared that He would meet with Moses and the Israelites at the Tabernacle and “abide” there. He would consecrate Aaron and his sons as priests, and sanctify the community of the Israelites by His Presence at the Tabernacle.

A square altar 1.5 feet long, 1.5 feet wide, and 3 feet high, was to be constructed of acacia wood and overlaid with gold for burning incense. It was to have a molding and rings of gold for wooden carrying poles overlaid with gold. The incense altar was to be placed just outside the curtain of the Holy of Holies where the Ark of the Pact [Covenant] was. Aaron would burn aromatic incense on it morning and evening while he tended the lamps as a consistent offering throughout the ages. Nothing else was ever to be offered on it, and it was to be purified once a year. It would be most holy to the Almighty.

Amongst our chachamim, rabbinical sages of blessed memory, there is a question about the order of this content of the Torah. Namely, why was the priesthood of Aaron and his sons, in particular the bigdei kehuna, the sacral priestly vestments that they would wear, mentioned before Aaron and his sons were ordained as priests? Originally the firstborn males were intended to be the priestly class. But in the next parasha of the Torah, Ki Tisa, the priesthood was seemingly transferred from the firstborns of Israel to the tribe of Levi due to the chet ha’eigel, the sin of the golden calf. So why would the Most High be describing the priesthood of Aaron and his sons before the golden calf incident?

Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki and Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, more commonly known as Rashi and the Rambam respectively, adhere to a simple explanation for this seeming discrepancy. There is an established principle for Torah interpretation defined as ein mukdam u’meuchar b’Torah, which essentially means that the Torah narrative is not always chronological in nature; the Torah will sometimes present its content in topical order or other format, even if that defies the chronological flow of events. Thus, Rashi and Rambam postulate that the Eternal One’s instructions concerning the priesthood of Aaron chronologically came later (after the chet ha’eigel, sin of the golden calf), but were documented here in the Torah in relation to the construction of the Tabernacle, etc. Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, or the RambaN, disagrees.

Similarly, Rashi and the Rambam indicated that the purpose of the Mishkan, Tabernacle, was to atone for the sin of the golden calf. By implication, if this grievous sin had not been committed by the early Jewish nation, the Tabernacle would have never needed to be constructed. Other rabbis, in particular Rabbi Don Yitzchak Abravanel as well as many of the Chassidic sages, counter that the original purpose for the Tabernacle was to facilitate a direct, intimate, and dynamic connection between the Eternal One and the Jewish people. The additional purpose of atonement was added after the sin of the golden calf. Indeed, even the common word used for “sacrifice” and “offering” in the Torah is korban, which comes from the Hebrew root meaning “to draw closer.” In other words, perhaps the very terminology of the Mishkan service and offerings indicated that the original purpose of the Tabernacle had always been to bring both righteous and unrighteous persons closer to the Almighty, either through offerings of gratitude and well-being or sacrifices for sin and atonement combined with proper teshuvah, repentance.

Returning to the original question regarding the timing and placement of the instructions regarding Aaron and his sons as priests, we can perhaps find a “compromise” answer for all the key viewpoints. In other words, perhaps it is not an “either-or” equation. One possible explanation relates to Aaron’s birth status. There are conflicting opinions as to whether or not Aaron or Miriam was older. Some Midrashic sources say Miriam was eldest, while other rabbinical sages, namely the RambaN and Rashbam (Rabbi Shmuel Ben Meir), seem to assert that Aaron was the oldest (although some claim that their intention was to say that Aaron was the oldest brother and not necessarily the oldest sibling). If we follow the presumed meaning of the RambaN and Rashbam, then perhaps the priestly role of Aaron was defined in the context of his role as a firstborn himself. In other words, Aaron and his firstborn son would be the most prominent firstborns among the original priestly class of firstborns. Several problems immediately arise from this theory, however. First, the other sons of Aaron are also mentioned as priests, who were clearly not firstborns. Also, the Torah already emphasizes that the priesthood would belong to Aaron and his sons for perpetuity seemingly with no regard for any firstborn status whatsoever (which mirrors the concepts presented by the Almighty throughout the Torah after the chet ha’eigel incident).

On a different but related matter, Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra commented that he felt that the Torah alludes to the fact that Aaron and his sons were worthy of the priesthood of their own merit, and not simply because the firstborn class was disqualified from their role due to the sin of the golden calf. In other words, Ibn Ezra is adamant that the Torah makes it clear that Aaron and his sons were not “second-stringers” to the firstborns; they did not become the priests only out of necessity and the reluctant “passing of the torch” to the next in line, so to speak.

In this context, we can examine two interesting possibilities. One possibility is that the priesthood was originally intended for Aaron and his sons and the firstborn males. Previously the Almighty through the Torah mentioned the firstborn males as being part of the priestly class as it was relevant to the striking of the Egyptian firstborn and the redemption of the Israelite firstborn. Now, as the Most High dictated the construction of the Tabernacle, He mentioned that Aaron and his sons would also be priests.

If this is so, however, then why didn’t the Almighty mention the firstborn males at all at this point of discussion regarding the priesthood? First and foremost, the entire Torah is truth, and therefore the narrative would naturally avoid any pending discrepancies. It would be highly inconsistent for the Eternal One to describe the bigdei kehuna of the firstborn, for instance, knowing that they would never wear them. But then why would the Most High ever appoint the firstborn as a priestly class in the first place? The original appointment of the firstborns as being designated for the Most High related specifically to the obligation that arose from the redemption of the slaying of the firstborn. But when it came time to actually consecrate the priestly class, the Almighty chose Aaron and his sons, and later the entire tribe of Levi. In other words, the obligation of the Jewish priesthood first rested with the firstborns, but the merit of the priesthood was ultimately earned by Aaron, his sons, and the tribe of Levi. The idea is that the Most High through the Torah was communicating the idea that the firstborn were obligated to be dedicated to Him in a special way because of their previous redemption in Egypt, but they were unworthy, as proven especially by the sin of the golden calf. Aaron and his sons, however, were always worthy of the priesthood, and therefore either it was passed to them. Or, due to their merit, they were always meant to be priests alongside the firstborn males; they retained their position after the firstborn males were disqualified and “dropped” from the priesthood.

There is another idea that could explain the appointment of the priesthood of Aaron and his sons in lieu of the firstborn males that could be simpler albeit more technical in nature. One of the aspects of the bigdei kehuna, priestly garments, was the tzitz, a small plate (frontlet) of gold on the forehead of the mitznefet, or turban-like headdress, of the kohen hagadol, the high priest. This golden frontlet was inscribed with the engraved words “Holy to the Almighty.” As Abravanel reiterates, this tzitz frontlet represented that the thoughts and intellectual powers of a man’s mind (namely the priest) were to be directed towards holiness.

Following the chronological narrative, Moses received the first instructions regarding both the Tabernacle and the priesthood of Aaron during the forty days and forty nights on Mount Sinai immediately after the original encounter with the Most High at Horev. As the next Torah portion, Ki Tisa, indicates, the Israelites couldn’t even wait for Moses to return before disobeying the Torah en masse. By the end of the forty days they had already adamantly insisted on ignoring the first commandments of the Almighty and instead engaged in heinous idolatry. As is obvious, the Israelites weren’t wholeheartedly dedicated to observing the Torah properly for thirty-nine days and then they woke up on the fortieth day and suddenly changed their minds. Rather, the Israelites had secretly intended to engage in idolatry for some time, and were dismayed to hear that idolatry was immediately prohibited by the Almighty. Thus, they reverted to idolatry at their first excuse, namely the presumption that Moses had delayed on the mountain. The point is that the intention and decision to revert to idolatry was already in the minds of the Israelites, including the firstborn males, before the sin of the golden calf. Similarly, at the end of the Torah in Devarim, Deuteronomy, 31, the Eternal One confirmed that the people of Israel were already planning to embrace idolatry at their earliest opportunity after the death of Moses, and Moses accused them accordingly.

Chronologically, this consideration would mean that the firstborn males (and most of Israel) had determined that they would not serve the Most High properly, but would instead be idolaters at the same time, or probably immediately before, the Almighty declared that Aaron and his sons would be the priests. In other words, perhaps the Almighty and the Torah narrative are subtly alluding to the fact that the firstborn males had already disqualified themselves from the priesthood by mentally planning to sin through idolatry. Or, more pertinently, perhaps the Most High was notifying Moses of the pending transfer since Israel and the firstborn males had already refused to take upon themselves the proper role of the priesthood through the Mishkan service, instead choosing idolatry. If the priests were required to keep their thoughts and intentions during spiritual service completely “Holy to the Almighty,” in this regard the firstborn males had already completely failed by lusting after idolatry and seeking to rebel against the Most High. Thus, the process of disqualification of the firstborns had already begun while Moses was on the mountain for forty days — to the point that the Almighty only described the priesthood as it related to Aaron and his sons — and the ultimately and official disqualification of the firstborn males was finalized and announced after they were caught “red-handed” in the act of shameful idolatry.

May the Holy One, Blessed be He, provide us with the methods and tools to bring ourselves closer to Him in every way. And may the Holy One, Blessed be He, ever strengthen us that not only our deeds are holy and in accordance with the Torah, but also the secret thoughts and desires of our hearts.