Genesis 44:18 – 47:27

(5-6 Minute Read)

Vayigash is a Hebrew word that means “and he drew near.” This Torah parasha, or portion, continues the narrative of Joseph as Judah drew near to his brother unsuspectingly and pleaded with him. He begged the viceroy, i.e. Joseph, to accept him as a slave instead of Benjamin. He explained that his father was so emotionally connected to Benjamin that if Judah did not bring him home, Jacob would die from grief.

Joseph could no longer control himself. He demanded that all of his attendants get out. Joseph sobbed so loud that the Egyptians could hear him. He said to his brothers, “I am Joseph. Does my father still live?”

The brothers could not answer Joseph out of shock. Joseph called his brothers closer, and explained the upcoming years of famine. He then sent them back to their father to explain that Joseph was now viceroy over all Egypt, and that the entire household should all come to him and live in Egypt in the land of Goshen.

He embraced Benjamin and wept. He likewise kissed and embraced his brothers, and only then were they able to speak with him.

The news reached Pharaoh that Joseph’s brothers had arrived; he and his courtiers were pleased. Pharaoh further ordered that the brothers and their households should come to Egypt and live there comfortably.

The sons of Jacob did so. Joseph sent them along with wagons and provisions for the journey. He gave each of his brothers a change of clothing, but gave several changes to Benjamin. Joseph sent them off with fine gifts, and admonished his brothers not to be quarrelsome on the way.

The brothers returned and told their father that Joseph was still alive and that he was the ruler of all Egypt. Jacob could not believe them at first. But when he heard their recounting of the events and saw the wagons that Joseph had sent, Jacob’s spirit revived. Jacob announced that his son, Joseph, was alive; he must see him before he died.

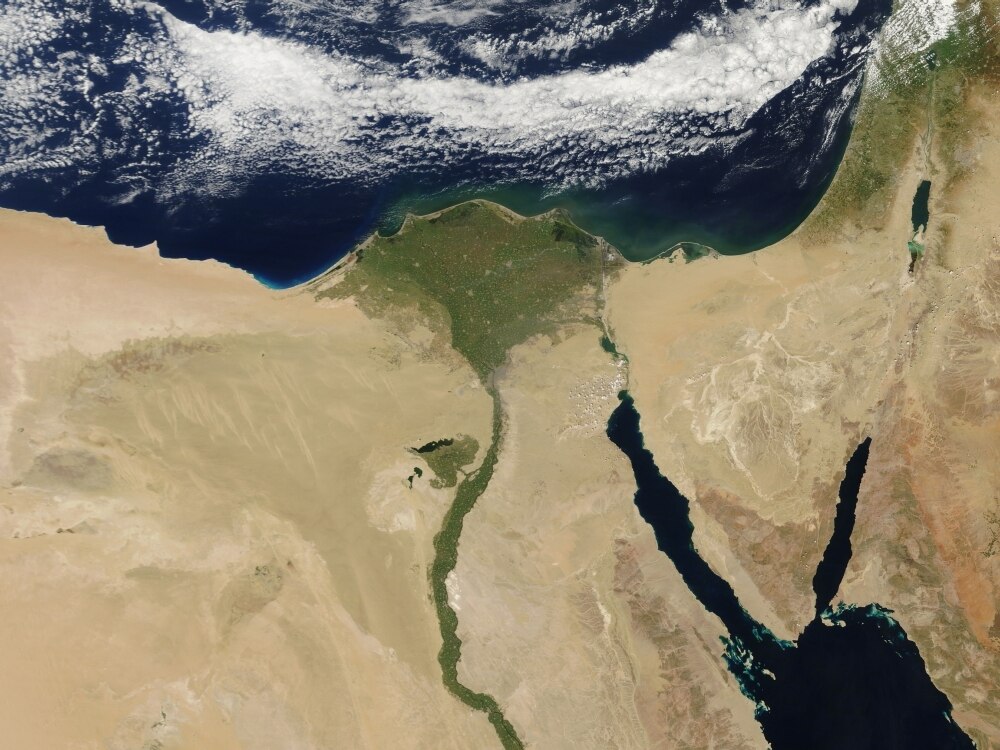

Jacob set out with his entire household from Egypt. On the way, he offered sacrifices to the Almighty in Beer Sheva. The Most High called to Jacob in a vision and told him not to fear to go down to Egypt. Jacob’s household and descendants would become a great nation. The Most High Himself would go down with Jacob and bring them back. And Joseph would be present at Jacob’s final days and burial.

The brothers loaded Jacob along with their families and possessions in the wagons and came to Egypt. The names of the members of Jacob’s household are outlined, especially grandchildren and other descendants — seventy souls in all.

Jacob sent Judah ahead to Joseph to guide them to Goshen. Joseph ordered his chariot to take him to Goshen to meet his father. Joseph embraced Jacob, weeping on his neck a long time. Jacob said, “Now I can die, having seen for myself that you are still alive.”

Joseph told his brothers that he would inform Pharaoh that they were shepherds by occupation, and that they should do the same. In that case they would remain in the region of Goshen, since the Egyptians abhorred all shepherds.*

Joseph reported to Pharaoh that his family had arrived, and he presented several of his brothers to him. Joseph and his brothers reiterated that they were shepherds presently located in the region of Goshen. Pharaoh welcomed the brothers to Egypt and approved their residence in Goshen; he even invited them to assist with the supervision of his own livestock.

Joseph brought Jacob to Pharaoh, who asked how old he was. Jacob replied that he was 130 years old, and that “Few and hard have been the years of my life, nor do they compare with the lifetimes of my fathers.” Jacob bade farewell to Pharaoh and departed.

Joseph settled his family in the choice parts of Egypt, including the region of Rameses. He sustained them all with provisions.

The famine was severe throughout the world, especially in Egypt and Canaan. Joseph gathered in all the money of Egypt as payment for the food rations. When the Egyptians ran out of money, Joseph requested their livestock as payment. After that, the Egyptians offered their land to Joseph in exchange for food. Thus, the Egyptians became serfs to Pharaoh. Joseph enacted a law that one-fifth of the harvest would belong to Pharaoh, while the Egyptians kept the rest. The land of the Egyptian priests, however, was an allotment from Pharaoh; they retained full possession of their land.

The household of Jacob, referred to as “Israel,” settled in Goshen of Egypt. They acquired holdings in it, were fertile, and increased greatly.

In Vayigash a question arises about the wagons sent by Joseph to his father to bring him and his household to Egypt. Besides the fact that this seemingly minor detail is mentioned repeatedly in the Torah, the question is asked why Jacob did not believe that Joseph was alive until he saw the wagons. How did the wagons prove to Jacob that Joseph was not only alive, but even the viceroy of all Egypt?

Rashi presents an interesting Midrashic idea, namely, that Joseph was studying the portion of the Torah discussing the eglah arufah. The mitzvah, or commandment, of the eglah arufah, or the calf with a broken neck, refers to the practice of finding a dead body outside of a city with no knowledge as to what happened to the victim. The word eglah is phonetically similar to agalot, the Hebrew term for “wagons.”

The RambaN discusses Rashi’s concept. He notes that this theory is a drash, or expanded interpretation, rather than a peshat, or straight-forward, simple meaning. Rashi’s hypothesis first assumes that the patriarchs had detailed knowledge of the Torah before Mount Sinai, which is Midrashic in nature and subject to further discussion. Also, the words eglah and agalot may sound similar, but in reality they are different words with no etymological relationship.

The Talmud does provide us with a more simplistic answer based on human psychology. The rabbis of the Talmud have reasoned that a person ostensibly does not lie about something if the truth of the matter will inevitably and easily be revealed. In other words, Jacob realized when he saw the wagons that it would have been senseless for his sons to have lied to him. After all, would Jacob’s sons have loaded their father and families into the wagons just to drive around in circles indefinitely? Or would they have taken their father and households to Egypt merely to prove that they had been lying when Joseph was nowhere to be found? Obviously not. And with that basic reasoning, Jacob knew that his sons were being truthful, and that Joseph was indeed alive.

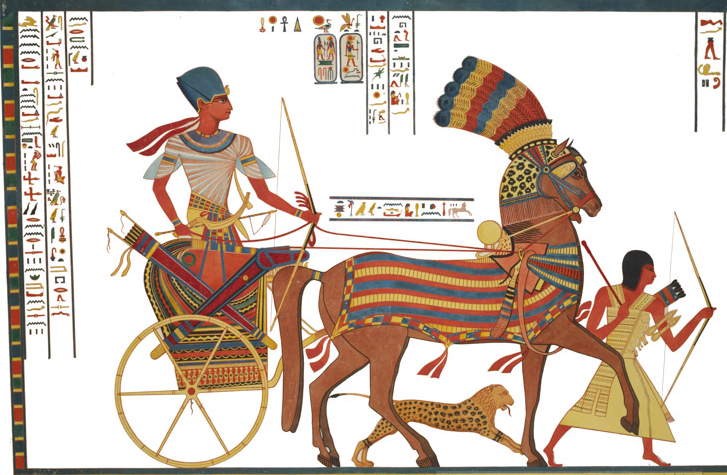

Some have expanded on this straight-forward answer with a series of thoughts regarding the nature of the wagons, chariots, horses, et al, of Egypt. All throughout the Torah and Tanakh narrative, the horses and chariots of Egypt are spoken of in negative terms. Indeed, the Almighty outlined in the Torah that all future kings of Israel were utterly prohibited from acquiring horses from Egypt (e.g Devarim / Deuteronomy 17:16). Besides the obvious factor that kings of Israel were to refrain from greedy excesses, another possibility is that the horses, chariots, et al, of Egypt were too inundated with pagan idolatry to be utilized. As hinted in Shemot / Exodus 9:3-4, 12:12, etc., and as commonly confirmed by various Egyptologists and archeologists, the Egyptians worshipped their animals, including livestock. Thus, we can reasonably connect the livestock of Egypt, including their horses, to idolatrous paganism.

This idea of Egyptian animal worship seems to be alluded to directly in the Torah text of this parasha itself. Joseph and his brothers repeatedly emphasize that the family occupation was shepherding in order to secure their residences in rural regions of Egypt, in particular Goshen (Bereishit / Genesis 46:31-34, etc.). Shepherds were abhorrent to the Egyptians because they worshipped sheep. (A similar analogy would be a cattle rancher and beef producer being given land in India away from the main population centers, since the Hindus consider the cow to be sacred.) One of the greatest false gods of Egypt was Khnum, represented by the sheep or ram. The context of the Exodus account and Ten Plagues (Shemot / Exodus 12, etc.) implies that the killing and eating of the Passover lamb was a direct affront to the worship of Khnum and proof that the Almighty was exponentially superior even to the supposedly “mighty” sheep-god of Egypt. Shepherds were therefore “abhorrent” to the Egyptians because they treated this supposedly “divine” creature like the common livestock that they actually were.

Later in the Tanakh in Melekhim Bet / II Kings 23:11, we read that righteous King Josiah did away with the “horses of the sun,” destroying and burning the affiliated chariots. In other words, the horses and chariots of the unrighteous kings of Judah, possibly obtained from sun-worshipping Egyptian pagans, were a great evil and a violation of Torah that was immediately eradicated by Josiah.

How do these passages and concepts relate to the story of Joseph and the wagons in question? Obviously Joseph was a righteous man who revered the Most High alone and shunned idolatry. He was also the viceroy of Egypt who had access to royal assets, such as horses, chariots, and wagons. It is inconceivable that Joseph would send horses and wagons to his father, the righteous and monotheistic patriarch, that bore idolatrous images or any other kind of connection to Egyptian paganism. Thus, some have theorized that Jacob finally believed the tales that his son was alive and the ruler of all Egypt only when he saw the royal Egyptian horses and wagons clearly stripped of all semblances of pagan idolatry. Pharaoh or any other Egyptian idolater would never disrespect their false gods and goddesses in such a manner. Only a righteous foreigner attaining a high position of unquestioned leadership, such as Joseph the Hebrew, would be capable of such an action. And these idol-free wagons were the evidence that Jacob needed to confirm the brother’s accounts that Joseph was both alive and in a position of great authority.

One of the lessons that we can derive from the story of Joseph, especially Vayigash, is trust in the Eternal One even in dark times. All throughout the narrative we read that “The Almighty was with Joseph,” even in such terrible circumstances as his unjust imprisonment (Bereishit / Genesis 39:21). As Jacob prepared to go to Egypt to reunite with Joseph and escape the famine, the implication of the text is that Jacob was deeply frightened. Presumably, Jacob was aware of the pending enslavement of his descendants as foretold by the Most High to Abraham in Bereishit / Genesis 15:15. And Egypt apparently was already notorious for enslavement. The Almighty acknowledged Jacob’s concerns. However, He did not tell Jacob that nothing bad would happen. Rather, the Most High assured Jacob that He would be with him and his descendants (just like Joseph). The Almighty would be with them, come what may, and ultimately bring them back to the land of Israel.

This is an important message to all of the Jewish people as the descendants of Israel. The Holy One, Blessed be He, has not promised us that there would never be challenges or hardships. He did, however, promise to be with us at all times, no matter what.

Interestingly enough, we see that the seeds of Egyptian slavery might have actually been sown during the rulership of Joseph. As the famine continued to rage throughout the world, the Egyptians first expended all of their money in order to buy food. After that, they sold their livestock, their land, and even themselves to Pharaoh in order to survive. While Joseph was ultimately benevolent in that he allowed the citizens to retain 80% of their earnings, Joseph nevertheless established a precedent of depriving citizens of their assets and making them both dependent and subservient on the government of Egypt. Later, when a new Pharaoh arose, possibly of a completely different dynasty altogether, he continued and expanded upon the same model. But in this case he targeted the Hebrews and was anything but benevolent; quite the opposite, in fact, and murderous slavery of the Hebrews ensued.

The Torah also notes that the Egyptian priesthood and religious leadership was immune to Joseph’s consolidation of assets and power due to a technicality in which the idolatrous clergy received their land and other benefits directly from Pharaoh. Thus, completely unintentionally, Joseph’s policies inadvertently made the idolatrous priesthood the most powerful entity in Egypt, both religiously and politically, second only to the level of Pharaoh himself and his courtiers. By the time the events of the Exodus story unfold, we see the level of power and influence of the pagan priesthood (e.g. Shemot / Exodus 7:22, 8:15, etc.). In other words, it is possible that the nature of the Ten Plagues, as the Almighty’s method of destroying the Egyptian priesthood and any sense of faith in these false deities, was partly necessary due to Joseph’s accidental advancement and even empowerment of the priestly class of Egyptian society.

Perhaps the greatest lesson of Vayigash is the power and dynamics of forgiveness. Joseph would have been completely justified if he had acted vindictively towards his brothers. He could have enslaved them — or worse — without any apparent criticism or consequence. However, Joseph instead chose to forgive his brothers and set a very powerful example for the entire Jewish people (and beyond). Instead of further destroying his family he instead chose to reunite them with both forgiveness and love.

One interesting aspect of Joseph’s forgiveness is that he didn’t forgive them immediately or unconditionally. He first analyzed through a series of tests their current state of mind and conduct. For instance, even as the disguised viceroy he gave Benjamin much greater favoritism than his brothers (Bereishit / Genesis 43:34, etc.), probably to determine if they treated him as poorly as they had Joseph. Why didn’t Joseph just forgive his brothers directly? Forgiveness does not require us to allow toxic behaviors or destructive actions into our lives. Oftentimes a person engaged in destructive conduct will insist that their victim is obligated to forgive them without the antagonist changing any of their behavior or actions. In other words, the offender purports that this “free forgiveness” is actually synonymous with a complete absence of accountability to continue indefinitely, which is absolutely not a Torah value. We can also see from the story of Joseph that this expectation is not valid. However, in contrast, if an individual is truly remorseful to the point of changing or eradicating the toxic or negative behavior, then following Joseph’s example, as difficult as it may be, is highly commendable.

But sometimes forgiveness can be hard, even if the one who wronged is sincerely repentant. After all, how did Joseph just “forget” about the seventeen years of abandonment, isolation, slavery, imprisonment, et al? The Torah tells us that Joseph didn’t “forget” about the hardships; he changed his perspective on them. He focused on the good that the Almighty brought out of the situation. In that context, he focused on the will of the Creator who engineered the universe — even the terrible actions of his brothers — for ultimate good. And with that perspective in mind, he was able to forgive his brothers after they properly showed their repentance for what they had done to him, recognizing that the Most High brought great good out of it.

May the Holy One, Blessed be He, always be with us even in the darkest of times. And may we be ever aware of His Presence with us, even when He seems far away. And may the Holy One, Blessed be He, give us the strength to forgive one another as appropriate. And by so doing may we actively restore and maintain healing and harmony in our homes and our communities.