Ecclesiastes 1:1-12:14

(3-4 minute read)

During the Jewish festival of Sukkot, sometimes called the Feast of Booths or Tabernacles, the book of Kohelet, or Ecclesiastes, is traditionally read. Written by King Solomon of Israel, Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) has the distinction of being the only true book of “philosophy” in the Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible.

The book of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) begins with the iconic statement of the thesis of the work: “Futility of futilities; all is futile!” Solomon declared that everything that happens “under the sun” is futile, vain, and a “pursuit of the wind.” Solomon noted that he had decadently embraced every possible form of pleasure, but then surmised that death strikes rich and poor, wise and foolish, all equally. There is a time and a season for everything, and that the Most High brings everything to pass at the proper time. Solomon also considered the suffering of the oppressed who have none to comfort them. Those who have many possessions ultimately have greater worries than those who labor daily. Sometimes the Almighty grants a man riches and property, but he is not permitted to enjoy them; rather, they are inherited or acquired by another. A good name is better than fragrant oil, and it is more advantageous to go to a house of mourning than feasting. The king of Israel also declared that in his life he had seen that sometimes a good man perishes despite his goodness, and sometimes a wicked man endures despite his wickedness. He found that the Eternal One had made humanity simplistic in many ways, but mankind had complicated themselves with too many intrigues. Wisdom is infinitely more valuable than folly, and no man can predict or prevent his death. Solomon additionally stated that while he understood that “all will be well for those who revere the Most High,” he lamented that the punishment of the wicked often seems delayed. Solomon advised that in the face of the inevitable finality of death, a person should enjoy the blessings of life with his or her spouse and family as the Holy One, Blessed be He, has permitted and granted. Wisdom is better than might or valor; but the wisdom of a poor and simple man is often scorned and his words are not always heeded. Just like a dead fly ruins an expensive ointment, so a little folly outweighs immense wisdom. Solomon encouraged the diversification of investments and assets, as well as the enjoyment of life and youth in the context of understanding that the Almighty will call us into account for our deeds. At the end of the matter, revere the Most High and observe all of His commandments in the Torah; for He will call everyone to account for their deeds, both good and bad.

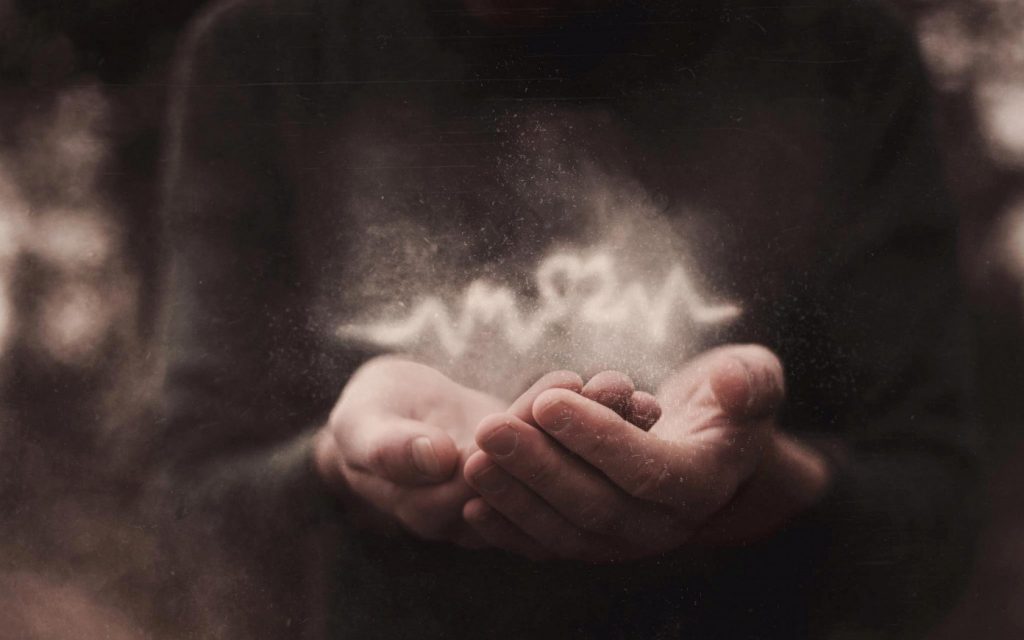

The core theme of Kohelet, or Ecclesiastes, is hevel. Hevel is a Hebrew word that literally means “fleeting dust,” and it is generally translated as futility or vanity. King Solomon, after years of “investigative research,” concluded that all the dealings of humanity “under the sun” are inevitably hevel, or vain futility. Since life is chaotic and unpredictable and ultimately results in death for all, Solomon encouraged his audience to enjoy life and the blessings of the Almighty while pursuing wisdom. Further, Solomon concluded that the purpose of mankind is to “revere the Most High and keep His mitzvot (Torah commandments).”

So how does this concept relate to the festival of Sukkot? Sukkot is most defined by the practice of building the sukkah, or traditional booth of the holiday. A sukkah is a temporary, square or rectangular structure with a roof consisting of a relatively thin layer of vegetative material, such as leafy tree branches. Vayikra (Leviticus) 23:42-43 states:

“You shall dwell in sukkot (booths) seven days; all that are home-born in Israel shall dwell in sukkot (booths); that your generations may know that I made the descendants of Israel to dwell in sukkot (booths), when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the L-RD your G-d.”

On the surface, the basic symbolism of the sukkah refers to the temporary structures that the Jewish people lived in during their wandering in the wilderness, as noted by Rabbi Eliezer. On a deeper level, as emphasized by Rabbi Akiva, the sukkah represents the Divine “clouds of glory” of the Shekhinah Presence of the Most High. Accordingly, the s’chach, or vegetative roof covering, of the sukkah serves as a form of a covering but must also be thin enough to enable the sukkah-dweller to see the clouds and stars of the sky.

Where does Rabbi Akiva derive the idea that a sukkah can be a metaphor for the “clouds of glory” of the Almighty? Elsewhere in the Tanakh the term sukkah is used in this way, in particular Tehillim (Psalm) 18:12.

“He made darkness His hiding-place, a sukkah surrounding Him; darkness of waters, thick clouds of the skies.”

The concept begins to form that the sukkah, similar to the Mishkan, or Tabernacle, is a temporary structure that relates to “housing” or “concealing” the Shekhinah Presence of the Most High, especially the emanation of His Divine “clouds of glory.” This is the direction of Rabbi Akiva.

Bringing this idea back to Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) and why we read this book on Sukkot, the essence of both Solomon’s philosophical treatise as well as the fall festival of booths is hevel, futility or vanity. The life of mankind, and indeed, “everything under the sun,” is fleeting as dust; it is temporary and destined for death and decomposition. It would seem that the logical conclusion is that if humanity and even life itself is so fleeting, then it is essentially meaningless.

Not so, says Solomon. Despite the chaotic futility of life and the world, the purpose of all creation is to “revere the Most High and keep His commandments.” All aspects of the universe, even the most fleeting components, have been created by the Almighty to connect with Him. And humans, especially the Jewish people, have been specifically tasked with a very unique method of connectivity: loving and revering the Eternal One, and keeping His commandments. And for the Jewish people, those commandments are defined by the entire Torah.

That is perhaps the deeper meaning of Sukkot, especially the custom of building a sukkah. The sukkah may be a temporary, fleeting, and even relatively flimsy structure. But that is precisely the instrument the Most High wants us to use to connect with Him. Similarly, our Creator has placed us in frail human bodies destined to die in a finite, limited world. But rather than abandon ourselves to reckless living in the face of our inevitable demise, Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) tells us instead to use our limited time and our “temporary structures” of healthy living in a physical world to connect with the Master of the Universe. The Mishkan, or Tabernacle, was an apparatus for the Jewish people in the wilderness (and beyond) to connect with the Almighty, and the Shekhinah clouds of Divine glory rested above it. The sukkah, or booth of Sukkot, is also a device to connect with the Most High as part of a festive celebration with the s’chach covering representing those same clouds of the Shekhinah Presence. And according to the principles of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes), the hevel, or futile vanity, of life and human affairs is yet another instrument for connecting with the Almighty. And, as Solomon noted, loving fear of the Most High combined with the observance of Torah is the proper and effective method of enacting that connection.

May the Holy One, Blessed be He, grant us to surround ourselves with the clouds of His Divine Presence just as we surround ourselves with the sukkah during the festival of Sukkot. And may He enable us to use all the hevel, or vain futility, at our disposal to further connect with Him through proper love, reverence, and Torah observance.