4-5 Minute Read

Exodus 10:1 – 13:16

Bo begins as the Almighty told Moses again to go to Pharaoh. The Most High had hardened the heart of Pharaoh and his courtiers to display His power and wonders, and that it would be told throughout the future generations. Moses and Aaron did so, relating that if Pharaoh refused to humble himself and let the Israelites go, locusts would cover the land and devour everything.

After Moses and Aaron left, the courtiers urged Pharoah to heed them. Pharaoh called them back, asking who would go. Moses replied that all would go — the entire family as well as the livestock. Pharaoh retorted that they were clearly bent on mischief, and that only the men could go.

At the Almighty’s command, Moses held out his arm over Egypt. An east wind brought an invasion of countless locusts. The locusts were a thick mass and consumed everything that had survived the hail.

Pharaoh hurriedly summoned Moses and Aaron and begged for forgiveness, asking them to plead with the Most High to remove the locusts. The Eternal One caused a shift in the strong winds and drove the locusts out and into the Red Sea. But the Almighty stiffened Pharaoh’s heart, and he would not let the Hebrews go.

The Most High instructed Moses to hold his arm out again, this time bringing a thick, tangible darkness. For three days the Egyptians could not see one another, or even get up from where they were. But the Israelites had light in their dwellings.

Pharaoh summoned Moses and said, “Go worship the Almighty, even your children. But leave your herds of livestock behind.” Moses countered that they would bring their flocks in order to make selection for offerings later, and that Pharaoh would provide them with additional livestock for sacrifices. The Almighty stiffened Pharaoh’s heart, and he refused to agree. He told Moses to depart, saying that he would die if he ever saw his face again. Moses replied, “You have spoken correctly; I will never see your face again.”

The Most High told Moses that He would bring one last plague, and then Pharaoh would drive them all out. The Hebrews were to borrow from their neighbors objects of silver and gold.

Moses declared that the Almighty would go forth at midnight and slay the first-born of the Egyptians, great and small, and also of the cattle. There would be a loud cry of grief in Egypt, such as never was and never will be again. Not even a dog would snarl at the Israelites. Then all of the Egyptian courtiers would beg Moses to depart along with all the people. And Moses left Pharaoh’s presence in great anger.

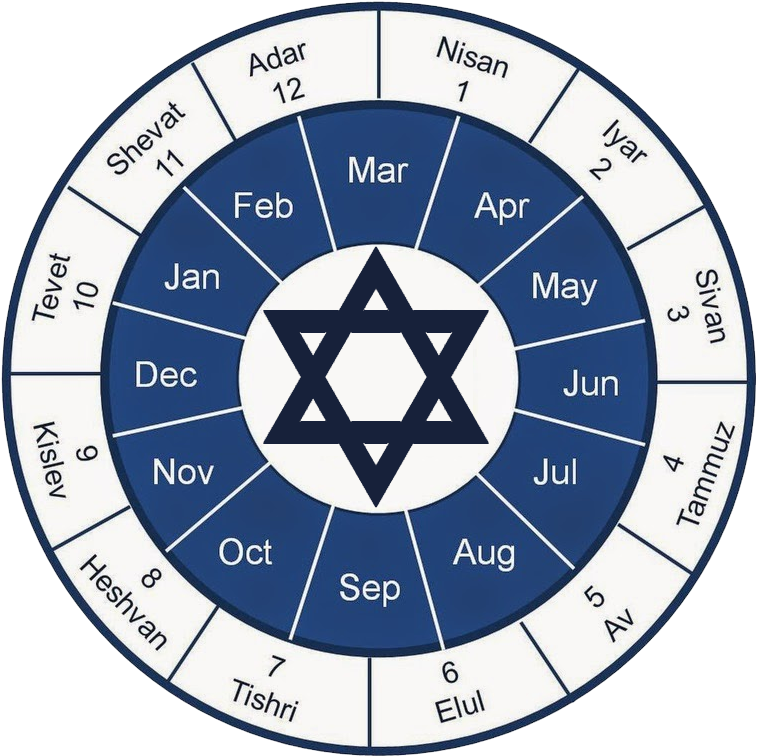

The Almighty stated to Moses and Aaron that this month (Nissan) would be the first month of the year. On the tenth of this month each Israelite family was to set apart a lamb for each household, or one lamb for two smaller households. The lamb was to be a year-old male without blemish taken from the sheep or the goats. The Israelites were to keep watch over it until the fourteenth day; then the assembled Israelites were to slaughter it as the sun set. Some of the blood was to be spread on the doorposts and lintels of the houses. The Most High commanded the Israeltes to eat the roasted meat of the lamb along with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. The lamb was to be roasted whole, and nothing should remain by the next morning. The meal was to be eaten in a rushed manner, with their sandals on their feet and their staff in hand. On that night the Most High would go through Egypt and strike down the firstborn, dispensing punishments against the false “gods” of Egypt. But the Almighty would “pass over” the houses with the blood of the goat kids or lambs on them. This day would be a remembrance and a festival throughout the ages and for all time. For seven days starting on the fourteenth day of that month at evening, all of Israel is required to purge their homes of leaven and only eat unleavened bread. Whoever of the Israelite community eats leavened bread during that time would be cut off from Israel.

Moses relayed the instructions of the Almighty to the elders of Israel. He further stated that the Israelites should use a hyssop branch to spread the blood, and they were not to exit their homes until the morning. The people of Israel did exactly as the Most High had commanded through Moses and Aaron.

In the middle of the night the Almighty struck down every first-born in Egypt. Pharaoh and his courtiers arose in the night, hearing a loud cry of grief; in every house there was at least one person who died, besides the cattle. Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron in the night and demanded that the Israelites depart from among his people, telling them to worship the Most High and be gone. The Egyptians also urged the Israelites to leave hurriedly, and the Hebrews took their unleavened bread. They further had borrowed silver and gold from the Egyptians, and they let them take whatever they wanted; thus the Israelites stripped the Egyptians.

The Israelites journeyed from Raamses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand men, besides women and children. They baked unleavened bread, since they had been driven out of Egypt hastily. At the end of four hundred and thirty years in Egypt, all the people of the Most High departed from there.

The Almighty told Moses and Aaron that uncircumcised foreigners were not permitted to eat the Passover offering. Only a foreigner who dwelled among Israel and was circumcised could eat of it.

The Almighty told Moses to consecrate every first-born male, both human and livestock, as His. Moses told the people to remember this day when the Most High freed the Israelites from the house of bondage with a mighty hand. When the Israelites entered the land of Canaan, which was sworn to their ancestors, they would observe the seven day festival of unleavened bread. They would explain to their sons (children), “It is because of what the Almighty did for me when I went free from Egypt.”

Moses explained that when the Israelites were brought to the land, they would sacrifice the first-born of the cattle to the Eternal One. The first-born son would be redeemed. And when their sons would ask the meaning behind it, the response would be, “The Almighty brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand and slew the first-born of the Egyptians.”

It would be a sign upon their hand and a symbol upon their forehead that the Most High redeemed the Israelites from Egypt.

One question that arises from the Torah parasha of Bo is the seeming anomaly that the Hebrew month of Nissan would be the “beginning of months,” but Tishrei (and Rosh HaShanah mark the beginning of the new year. How is it possible to have two new years? And what is the purpose and benefit of two new years?

First, on a simpler level, even in the secular world we have numerous “new years” that don’t always coincide with the first day in January. For instance, the new school year begins in the fall, and the fiscal year is marked by the first of July. Thus, even outside of Judaism a principle is established that a new year by the calendar and a new year for a specific purpose don’t always coincide.

Beyond that, there is the possibility of a deeper significance. There is an issue of direct relevance to the observer. Rosh HaShanah is the head of the year because our Midrashic tradition tells us that the first of the month Tishrei was the day that the Almighty finished creating the world. Therefore, it is only logical to maintain the years from that point, since that is the day that history and the calendar officially began.

On the other hand, the exodus from Egypt recounts the birth of the Jewish people as a free nation. The Jewish people did not observe the creation of the world; they did, however, witness the “mighty hand” of the Most High Who redeemed them from Egypt. The exodus from Egypt was, in a sense, the “beginning of time” for the Jewish people on a level that was both personal and relevant. Thus, on the one hand we count the years from the creation of the world; on the other, we designate time from the birth of our nation following our redemption from Egypt. Both events are crucially important and central, and therefore we note both simultaneously.

Another indicator of the relevance factor can be found in how the Almighty addressed the Jewish people in His first utterance from Mount Sinai. The Eternal One declared, “I am the L-RD your G-d Who brought you out of Egypt, the house of bondage…” (Shemot / Exodus 20:1) As our chachamim, rabbinical sages of blessed memory, note, the Most High didn’t use a term such as “I am the L-RD your G-d Who created the world,” for instance. Rather, He chose a term that was directly relevant and relatable. Each and every Jewish man, woman, and child could relate to the Almighty as their Redeemer from Egypt in a very personal way. And this relevance could also be the motivation behind declaring that Pesach (Passover) is the “beginning of the months.”

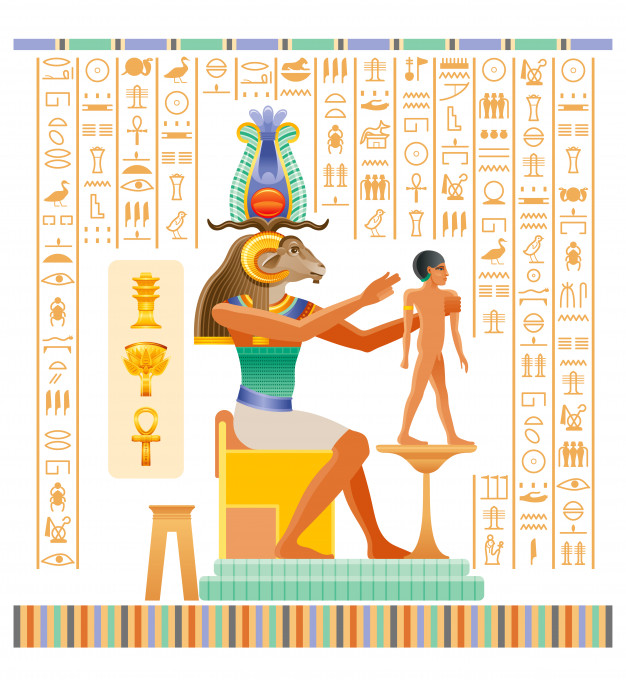

The Almighty made an interesting comment in Exodus / Shemot 12:12. He stated that He would “mete out punishments against all of the ‘gods’ of Egypt,” especially by killing the first-born. But this brings us to an obvious question: if the deities of Egypt were fake, then how could they be punished? Further, how did the death of the first-born humans and cattle affect non-existent false gods?

In order to understand what the Eternal One seems to be indicating, it is important to understand the nature of Egyptian paganism and idolatry. Each of the ten plagues “attacked” an Egyptian “god” or “goddess”; or, perhaps more accurately, the ten plagues destroyed any faith or confidence in these false deities. For instance, several “gods” were associated with the Nile. When the Most High turned the Nile to blood, He proved unequivocally that He was greater than any so-called “god of the Nile.” Similarly, the plague of darkness devastated the belief in even the supposedly “mighty sun god,” Ra. Such was the case with all of the plagues, including the death of the first-born and the killing and eating of the Pesach lamb or goat kid. One of the greatest of all Egyptian false “gods” was Khnum, represented by a combination of a human and a sheep or ram. Khnum was allegedly the creator and empowerer of all other “gods,” which, according to Egyptian fallacy, would have supposedly included the G-d of Israel. By the time that ten plagues approached their climax, the Egyptians presumably were placing all of their faith and trust in Khnum, worshipping him and begging him to “revoke the power” or otherwise destroy the Almighty G-d of the Israelites. In response, the Most High commanded the early Jewish people to make a public display with their lambs or goat kids for four days, then roast them and eat them. In other words, while the Egyptians were virulently worshipping sheep in honor of Khnum in a “final showdown” against the Israelite G-d, the Almighty instructed the Jewish people to literally barbecue the so-called “god” of the Egyptians. Thus, the killing and eating of the Pesach lamb or goat kid and the ensuing spreading of the blood on the doorposts was actually a very visible symbol of a complete rejection of Egyptian idolatry. In order for the Jewish people to truly leave Egypt, the “house of bondage,” both physical and spiritual, and ultimately receive the Torah, they needed to fully separate themselves from all forms of Egyptian idolatry.

Additionally, the Egyptian priesthood was taken exclusively from the first-born sons. And Khnum was supposedly the giver of all life, including to humans as well. By striking the Egyptian first-borns at midnight, the Most High utterly destroyed the entire idolatrous priesthood in a single moment. Thus, the Almighty showed the Egyptians beyond any possible denial (or perhaps, d’Nile) that He was and is the Almighty Creator, and destroyed their ability to worship the powerless and non-existent “deities” of Egypt.

Another aspect of the parasha is that we see perhaps the first example of Halacha, or Rabbinical injunction based on the Torah. The Most High gave Moses a set of commands for the early Jewish people on how to properly observe the first Pesach. One element was the spreading of lamb or goat kid blood on the doorposts. However, the Eternal One is not recorded as saying how to spread the blood. Rather, Moses explained to the elders of Israel what the Almighty had required, and then provided guidelines on how the Jewish people could best perform the commands of the Eternal One. Much of Halacha takes a principle commanded by the Most High and explains the “best practices” for how to accomplish that. For instance, in Deuteronomy / Devarim 6 we are commanded to bind the word of the Most High upon our doorposts, which is thematically similar to placing the “anti-idolatry” blood of Pesach on the doorposts. But this command is somewhat abstract; how does one accomplish this? The chachamim, rabbinical sages of blessed memory, have therefore set a precedent that the established method according to Halacha is to insert a hand-written scroll of parchment containing a key passage from the Torah (namely part of Deuteronomy / Devarim 6) in a protective case on the doorpost. Like Moses, the rabbis have expanded and explained how to best perform the Almighty’s instruction without adding to, deviating from, or contradicting the original command.

May the Holy One, Blessed be He, enable us to connect with Him in a direct and relevant way, recognizing all of the blessings that He bestows upon us each and every day. And may He ever redeem us from our own personal “Egypts,” both physical and spiritual, in order to reach higher levels of connection and Torah observance.