(5-6 Minute Read)

Thousands of Jews listened intently to the English words reverberating out of the speakers of countless radios all throughout Tel Aviv and other Jewish cities. The audience waited with bated breath, silently adding the tally of the votes.

“United States, Yes. Canada, Yes. Saudi Arabia, No. Australia, Yes…” the American voice droned on in an emotionless monotone, as if he was completely unaware of the momentousness of the occasion.

Finally all of the votes were counted. The member states of the United Nations General Assembly had voted on whether or not a modern Jewish state should be established in the land of Israel, at that time referred to as the British Mandate of Palestine. And the verdict was that a Jewish nation should be created, although the territory allocated to the Jewish people was subpar and less than anticipated.

Regardless, the Jewish residents of the land broke out in joyous celebration. Bottles of champagne popped open. Dancing erupted in the streets. Large bonfires were lit in rural communities.

The Arabs, however, were outraged. They argued that the Jews were not entitled to a single scrap of the land of Israel. Accordingly, the next day large mobs of Arabs came out in droves against the Jewish population, looting stores, destroying property, attacking buses, and otherwise engaging in acts of violence against Jewish targets. The Arabs never agreed to the UN partition plan of 1947.

This wasn’t the first time a modern Jewish state had been promised. The ruling British had issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917 which called for a 20th century Jewish state in the entire land of Israel, and for an Arab state in what is now Jordan. However, due to pressure and criticism from the Arab and Moslem populations nearby, the British went back on their promise for a modern Jewish state while eventually granting the Arab populations to establish independent nations. But this time it would be different; this time the Jews wouldn’t allow the British or the rest of the world to change their minds.

Following the United Nations vote in November of 1947, the British government had committed to withdrawing completely from the land of Israel, referred to as the British Mandate of Palestine, by the following May less than six months later. In the meantime, the Arabs broke out into waves of riots and violence, and essentially started a civil war. The British usually turned a blind eye as Arab forces attacked Jewish targets, mostly civilian. Previously, the Haganah and Palmach as well as other Jewish defense organizations were generally opposed by the British, and they often operated in secret to protect Jewish communities and defy British orders against Jewish immigration to the land of Israel. Now David Ben-Gurion and other early leaders engaged in the daunting task of transforming a clandestine paramilitary organization into an organized army. Similarly, the Haganah worked tirelessly to smuggle military-grade weaponry into the land of Israel and get it into Jewish hands, especially old German fighter planes from Czechoslovakia. Before and after the British withdrawal, the British had vehemently prohibited the Jews from acquiring any weapons, and even encouraged an embargo of the region sponsored by the United Nations. Meanwhile, in many cases the British sold their surplus weaponry to the Arab neighbors hostile to the Jewish population, especially before the withdrawal. Thanks to the British, the deck had been heavily stacked against the Jewish defenders in the land of Israel.

In the six months or so between the United Nations vote and the full British withdrawal, the Arabs both inside of the British Mandate of Palestine as well as their allied Arab neighbors aggressively attacked the Jewish population. Meanwhile, various armed Jewish organizations attempted to defend these communities. As the British began to withdraw, the Jews counter-attacked the Arabs and expanded Jewish control into new territory. A particular focus was placed on providing relief to the besieged Jewish residents of Jerusalem, but these efforts were often unsuccessful. As the Jewish defenders pushed back the Arab attackers, several hundred thousand Arabs fled to their neighboring nations. Some have claimed that the neighboring Arab leadership requested that they leave in order to clear the area for their military operations. Others say that panic swept the Arab population, fearing that the Jews would reprise the Arabs after the atrocities they committed against the Jewish people, such as the Hebron Massacre of 1929 and the Arab Riots of 1936-1939. Some have claimed that the Jewish forces intentionally drove out the Arab residents, but these accusations are disputed. Also, many of the perpetrators of violence against the Jewish people were resident Arab “civilians,” so it is unclear how many of these fleeing Arabs were actually violent albeit disorganized combatants.

By May of 1948, the British began to finalize their withdrawal. Jewish forces entrenched themselves, waiting for the pending onslaught of numerous Arab armies against them. On May 14th, 1948 David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the Declaration of Independence in Tel Aviv, and officially established the State of Israel as the last British forces vacated the land through the port of Haifa.

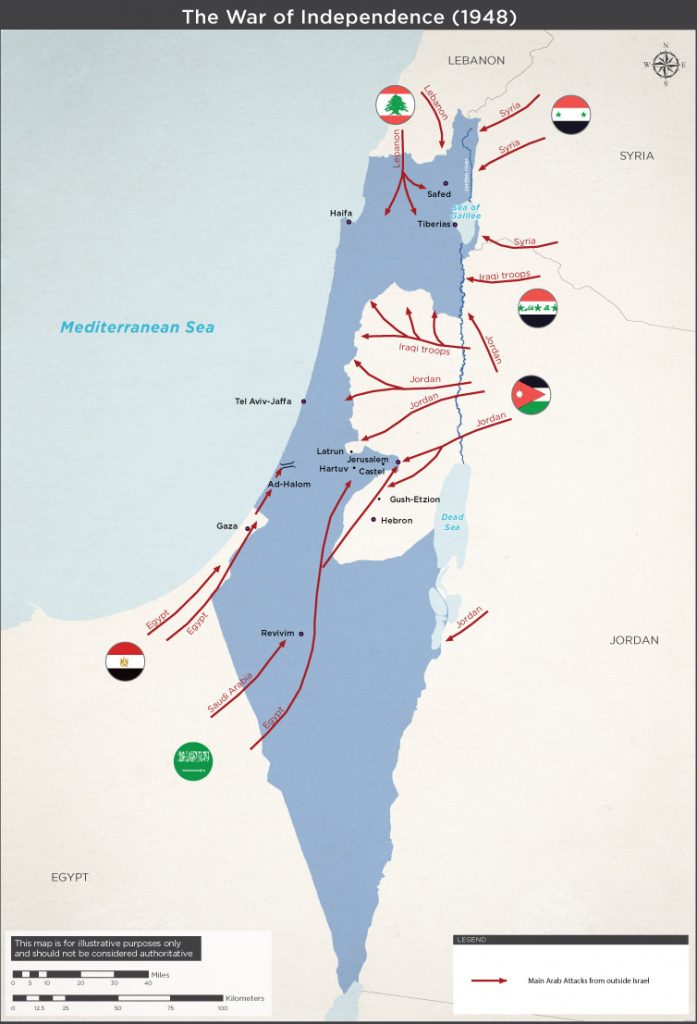

The surrounding Arab nations immediately launched a massive assault against the brand-new Jewish state. Armies from Transjordan (Jordan), Egypt, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen all converged on the small strip of land the size of New Jersey. The Israel Defense Force, consisting of the Haganah forces and their reluctant allies, the Irgun and the Lehi, worked to repel the invading Arab armies and paramilitary forces.

After approximately ten months of fighting and three failed cease-fires, the Israeli forces had successfully defended the Jewish population from the allied Arab attack. Egypt, Lebanon, Transjordan, and Syria each signed separate armistice agreements with the new Jewish state. Israeli forces controlled much of the land of Israel, while Transjordan and Egypt annexed the West Bank and the Gaza Strip respectively. At no time did either of these nations even consider the establishment of an independent Arab state in these territories called “Palestine.”

David Ben-Gurion and the early Zionist Jewish leadership first declared an independent state in the land of Israel over seven decades ago 1948. Since then, neighboring Arab nations have launched several invasions and started multiple wars. And the Arabs living in the disputed territories, now called “Palestinians,” have engaged in seemingly endless waves of violence and terrorism. And even now the dispute continues, with Arabs attacking Jewish civilians and the Israel Defense Force launching counter-terror operations.

There is another side of the coin that is often not fully discussed in regards to the early Zionist movements. Initially, and even in the present day to a degree, there was a rift between the secular Jews and the religious Jews in regards to the establishment of the State of Israel.

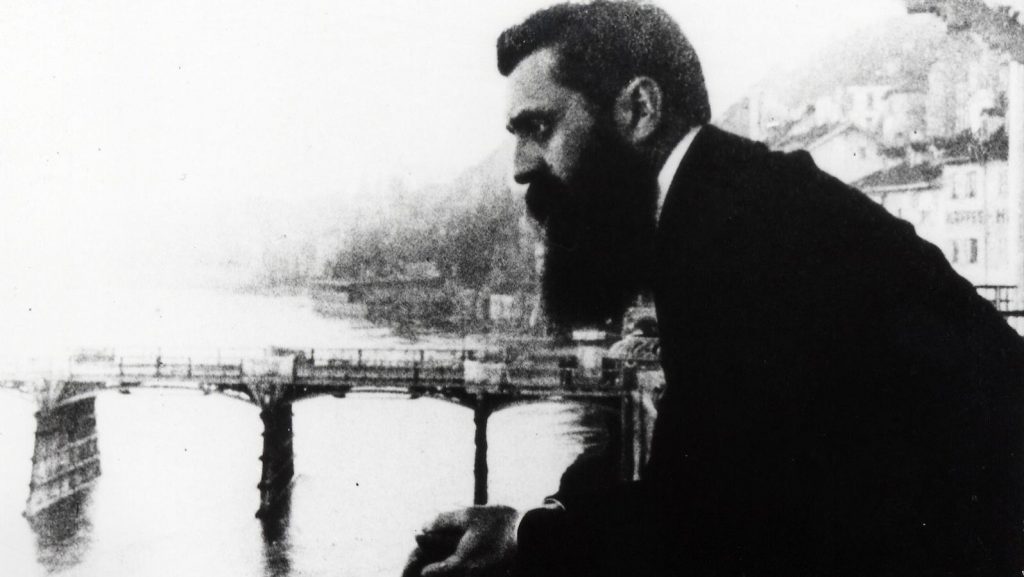

While the topic is infinitely complex, the simple version is that the early Zionist Jews were intensely secular and even anti-religious in many cases. Theodor Herzl is often credited as being the “founder” of the idea of a modern Jewish state. However, Herzl’s vision for a “Jewish state” in many ways did not reflect the coexisting plurality we have today in which secular and religious Jews live side by side in harmony (for the most part). Similarly, Herzl was hardly the first or only advocate for a modern Jewish state in the historical land of Israel, although that is a common misconception.

In many ways the caution of the religious Jews regarding the establishment of a Jewish homeland related to the timing and more importantly the quality of this theoretical state. The religious Jews wanted to ensure that any future Jewish state would be exactly that — Jewish. The religious Jews emphasized the importance of the quality of this proposed state, in which the population existed culturally, spiritually, and traditionally on a relatively high plane. Some were concerned that Herzl merely wanted “a state of Jews,” rather than “a Jewish state.” In other words, if a nation were to be created, the religious Jews wanted the entity to be a high quality entity characterized by strong Jewish culture, tradition, and religion. In contrast, Herzl’s idea of a “Jewish state” was a completely secular entity in which the inhabitants merely happened to be Jews who were all but unrecognizable as such, a “coincidence” facilitated by growing antisemitism in Europe and beyond.

It should be noted that the concerns and criticisms of the religious Jewish community of Theodor Herzl, the alleged “founder of Zionism” were not unfounded. Most of his life Herzl boasted of immoral exploits and shamefully admitted to the contraction of venereal diseases. His oldest daughter suffered from mental illness and drug addiction, eventually dying of a heroin overdose. Herzl refused to circumcise his son, who later converted to several forms of Christianity and ultimately committed suicide on the day of his sister’s funeral. In the suicide note, Herzl’s son lamented that there was no one left to say kaddish for him after he had said kaddish for his parents and sister. The point is that the religious Jewish community had reasonable grounds to be concerned about what a “Jewish state” created by Herzl and his family would look like in reality.

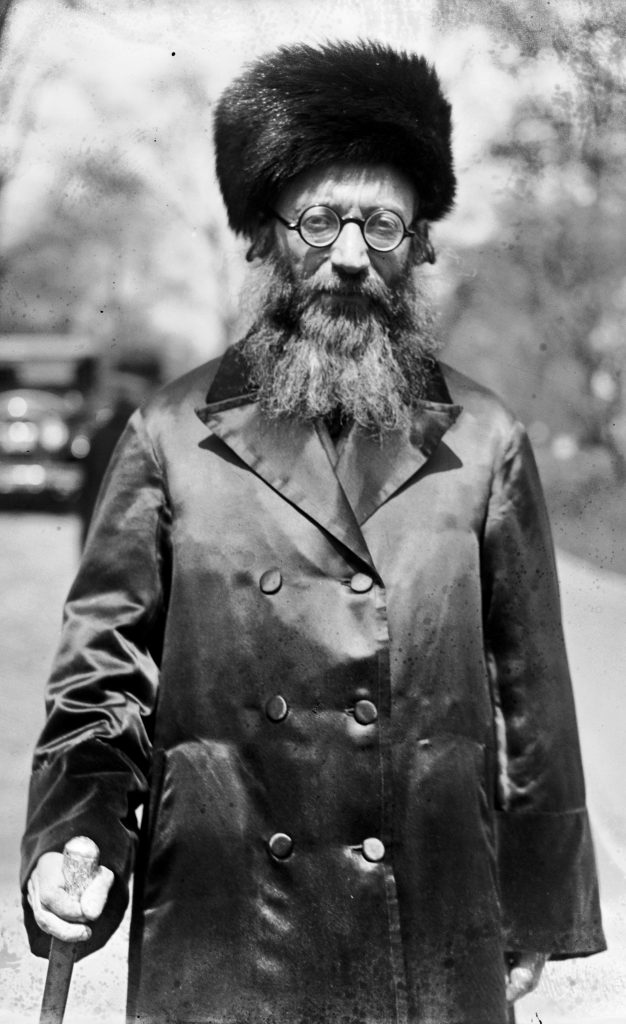

Throughout the past century religious Jews have discussed and debated the best ways to interact and cooperate with the modern and secular State of Israel, especially as the State of Israel and the ideology thereof has evolved significantly since its founding. Rav Avraham Yitzhak Kook Z”L, who passed away in 1935, had a revolutionary viewpoint on religious coexistence with secular Jews living in the land of Israel as well as their political aspirations. His perspective was very deep spiritually and kabbalistic, but a simplified version could be defined as the belief that sometimes the Almighty uses imperfect people or even negative actions to achieve His will. An example would be the brothers of the Biblical Yosef (Joseph) who were sold by his brothers into slavery (Bereshit/Genesis 37). However, the Holy One, Blessed Be He, uses the incident to bring Yosef to a position of prominence, saving Egypt and the nearby regions from severe famine. In other words, Rav Avraham Kook Z”L focused on the resulting good rather than the imperfect human instruments thereof.

Perhaps the best approach to the topic of religious Jews relating to and cooperating with the modern version of secular Zionism was stated by Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, the former Chief Rabbi of the [British] Commonwealth. In his book, Tradition in an Untraditional Age, Rabbi Sacks queried:

“If Jews were condemned to die together [in the Holocaust and beyond], shall we not struggle to find a way to live together?”

As we commemorate another anniversary of the creation of the modern State of Israel, perhaps we can all successfully “struggle to live together” in peace and harmony with the blessings of the Almighty. Our victory can only be achieved through unity.