(7-8 Minute Read)

I had grown up as a relatively simple American girl. Or, at least, my life seemed simple on the surface. I was born into a Roman Catholic family in New Jersey, and my father of French and Slovakian heritage served in the United States Armed Forces and later continued to work with the military as a civilian on various forts and installations.

My mother was an interesting mixture ethnically. Her father was part African-American, being the descendant of an emancipated slave woman. And he was also a registered Native American. He had served in the US Army in Europe during World War II and afterwards as a postal deliveryman. While deployed overseas, he met my maternal grandmother, a German and Czech refugee of the war. He married her and brought her to the United States.

My grandmother never talked much about her life in Europe before she immigrated to the United States. Both sets of my grandparents practiced Roman Catholicism, albeit somewhat unenthusiastically. My own parents also adhered to the Roman Catholic faith and raised me and my siblings accordingly, but with varying degrees of sincerity and interest over the years.

I was now in my mid-twenties. I had earned a bachelor’s degree and obtained a career-level job in professional communications. I had my own apartment, my own car, and excellent credit. But I was woefully single and even a bit inexperienced in the dating world.

My mother worked part-time for a company contracted by the United States Army to provide training programs and supporting logistics to the military. In turn, this company hired local civilians, including my mother, to supplement their operations on a part-time basis.

One day my mother announced to me, as many mothers often do, “I just met the perfect guy for you!” She was referring to her manager, an American-Israeli man about thirty years of age who worked for the company contracted by the Department of Defense as a training program manager and logistics coordinator. He had served in an elite unit of the Israel Defense Forces and been engaged in combat operations, and he now worked with the American military. More important to me, however, he was tall, dark, and handsome. He was intelligent and confident with a kind yet mischievous smile.

But there was a slight problem. He was Sephardi Jewish and Torah-observant at a modern Orthodox level. I was a Roman Catholic girl of European, Native American, and African-American ancestry. Although my mother intrusively established a Facebook connection without my full consent, the handsome Israeli military consultant did little to interact with me at all, let alone show any kind of actual dating interest. And I didn’t push it, either. After all, we were completely incompatible from the start. For over a year I didn’t even meet him in person.

Eventually, the training program was short-handed on a certain occasion, and they needed to recruit a few more employees for a short-term contract. My mother talked me into showing up for an open interview. I wasn’t even planning on following through with accepting the extra work (since I already had a full-time job). But I wanted to finally meet the Israeli man my mother couldn’t stop raving about.

I nervously entered the conference room at a local hotel and then I saw him. I swallowed hard; my mother hadn’t been exaggerating with her gushing approval. He immediately approached me and my mother and engaged us in a warm and friendly conversation. Although I hadn’t expected to, I was persuaded to work some extra hours for the military training company. After all, how could I refuse?

Over the next few months as an on-call, part-time employee, I interacted with the transient Israeli military contractor. We immediately hit off a friendship and workplace connection. On my own end, I could feel myself falling for him more and more. The sparks began to fly. And I could tell that he was hardly immune from the palpable chemistry and budding connection between us.

But again, there was a problem. He was a Torah-observant Sephardi Jew. He kept Shabbat, kosher, and other religious guidelines that were completely foreign to me. And he had zero interest in starting a serious relationship with a non-Jewish girl. I was sure about my growing feelings for him, but I also wasn’t sure about how we could make a relationship work.

After several months, he began to try to push me away. In fact, unbeknownst to me, he had even set a deadline to cut off all contact and interaction with me altogether, fearing that I was becoming too interested and getting too attached.

In what he had secretly decided was supposed to be one our last conversations, we were speaking on the phone. I relayed an unusual event that happened to me the evening prior, and it sparked a discussion about our family backgrounds. I explained to him that my father was of European heritage, and that my maternal grandfather was Native American and African-American, while my maternal grandmother was German and Czech.

“What did your German side of the family do during the war?” he asked in his pleasant way. “And I hope you are not going to tell me that they were part of the SS,” he said mostly jokingly, but not entirely.

“No,” I responded with a chuckle. “They were refugees fleeing the Nazis.”

“Fleeing the Nazis?” he replied in surprise. “What do you mean?”

I then recounted the little bit of our family history that I was aware of, which wasn’t much. My grandmother had been a young girl during World War II. They were Czech citizens who had been living in Germany. As the Nazi persecution intensified, her father was arrested and taken away from the family. He was later shot in the woods, but my grandmother would never tell us why. My grandmother herself along with her own mother and grandmother were removed from their home. The Nazis came to their house and gave them one hour to pack their belongings in a single suitcase. My grandmother recounted that she had a favorite doll that she was forced to leave behind, since they had no room in the suitcase. The family also hid their valuables in the attic, hoping to recover them when they returned. My grandmother then described fleeing and returning to Czechoslovakia with other refugees. At one point they were living in a field. Starving, they dug into the cold dirt in order to find raw potatoes to eat. My grandmother later returned to her family’s home after the war. She expressed how angry she was when she saw that the home was now occupied by an unknown German family, who also presumably had stolen all of their valuable possessions and family heirlooms.

There was a long pause, and then he asked, “Why was your mother’s side of the family fleeing the Nazis?”

“I don’t know,” I answered thoughtfully and maybe even a bit lamely. “She never really told us that part of the story, and we never really asked.”

“And what, may I ask, were the names of these ancestors of yours on your mother’s side who were fleeing the Nazis?”

I then repeated some of the names of my grandmother’s family, which I soon found out were very typical Jewish names.

The Sephardi man who I had come to futilely have affections for sat on the other end of the line in near silence for a long moment after an exclamation of shock and surprise. He immediately began searching the internet on his smart phone to collaborate the information I had told him. Sure enough, my family and relatives had been thoroughly documented in several databases of Jewish Holocaust victims and survivors. Similarly, one of my ancestors on my mother’s side was documented as one of numerous Jewish or Jewish-connected professors who were ultimately forced out of the universities in Germany by the Nazi regime and made an exodus to British and American schools.

My family confronted my grandmother about the evidence we had discovered about my maternal Jewish heritage.

“Are we Jewish?” we asked her directly.

“Well, of course we are Jewish,” my grandmother responded, as if somehow we should have already known the secret that she had been hiding from us her entire life. “That was just a very difficult time, and I don’t like talking about it.”

I didn’t understand what all of this information meant at first. My reluctant Israeli love interest explained to me that this revelation meant that my grandmother was a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust, and that meant that I was, in fact, Halachically Jewish myself. Such being the case, although he had made it clear to me previously that he would not pursue any kind of romantic connection with me, he emphasized that “this changes everything.”

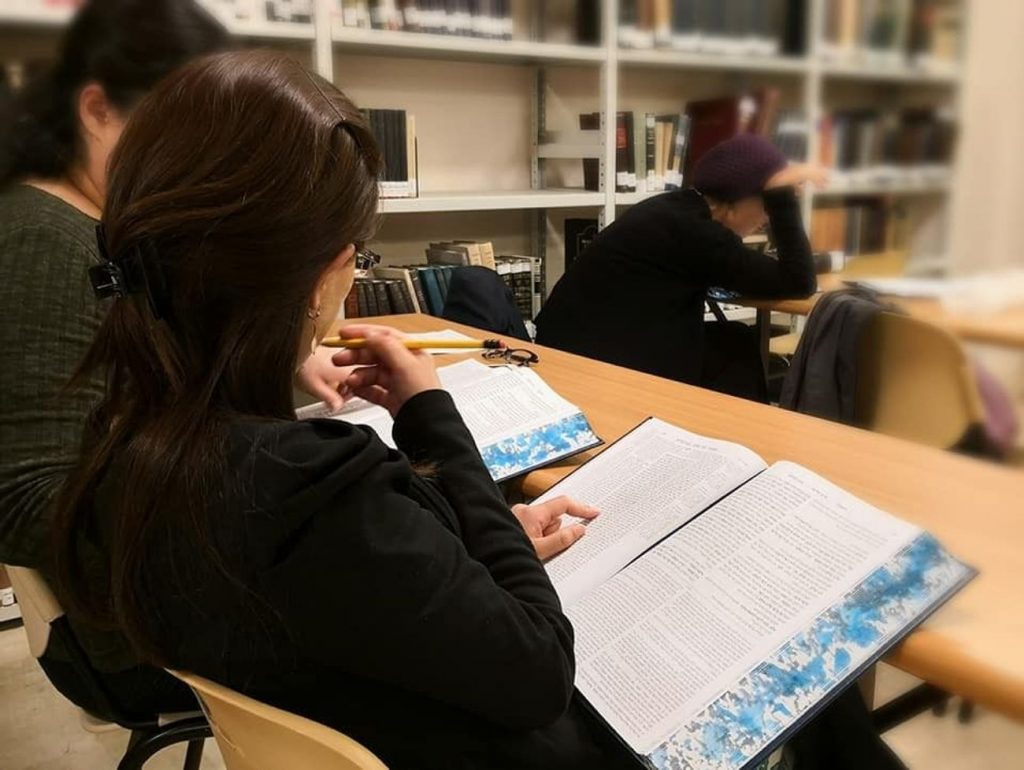

Although I was thrilled that, despite my wildest expectations, I could now enter into a dating relationship with this handsome Sephardi man, we both agreed to take things slow. He expressed to me repeatedly that it was very important to him that my connection with G-d through Judaism and the Torah be sincere and independent, and not just something that I did because I felt like he wanted me to. Almost immediately I became shomer shabbat, keeping the Sabbath according to traditional guidelines. I also observed kashrut, or kosher dietary laws, and even worked to make my kitchen kosher. I also began a long, arduous process of obtaining further documentation establishing my Jewish identity in a Halachic sense according to rabbinical regulations.

The more I practiced Judaism, the more I fell in love with it. Having a connection to G-d was always very important to me, but my connection through Judaism was vastly superior to anything I had ever experienced through the formula of Roman Catholicism. Also, I engaged in careful study of the Torah, especially by reading the entire Torah according to the weekly parshiot, or portions, and studying them in-depth. I soon came to an undeniable realization that Roman Catholic teachings are completely incompatible with the clear text of the Torah. If I was to believe that the words of the Torah came from G-d Himself and that the commandments and teachings thereof were still relevant to the Jewish people today, then I would have no choice but to completely and utterly reject Roman Catholicism. While this was obviously a process, it didn’t take long for me to adopt Judaism fully. Truth be told, when I think about some of the teachings of Roman Catholicism that I once endorsed, I can’t fathom how I believed some of them. It’s kind of embarrassing, actually.

After a year and a half of dating and more firmly establishing my observance of the Torah, we were married. And after much further discussion, my Sephardi husband and I have decided that we would like to build our new family in Israel. We understand that it will be challenging in many ways, but the more we think and pray about it, the more we feel that it is the right choice for our family. Also, since my husband is already Israeli, we have noted that we have some existing infrastructure, and he could even have better career opportunities than in the United States.

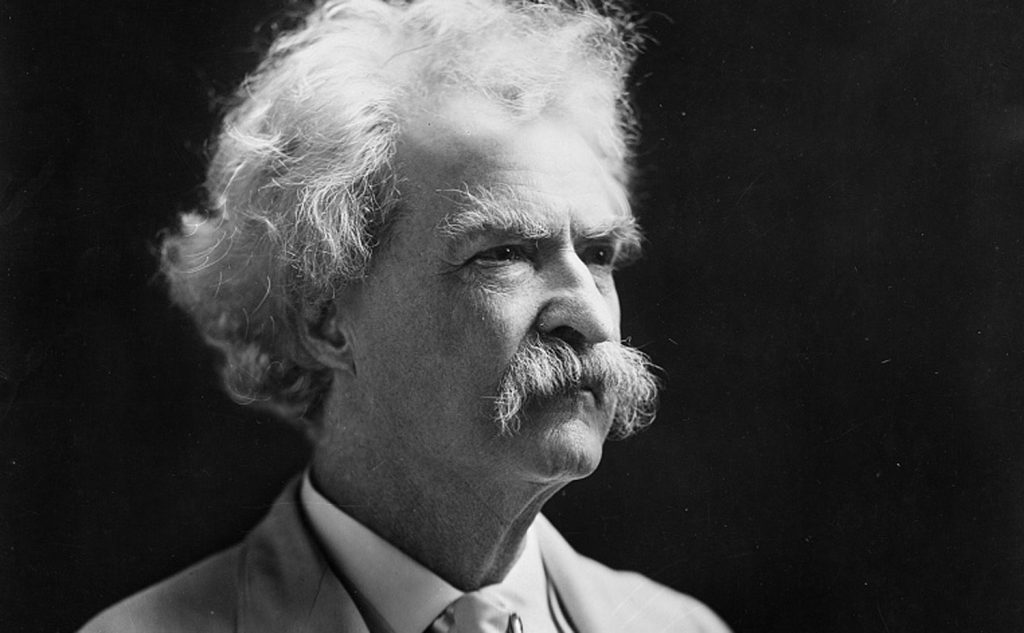

As Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Memorial Day, draws near, I am marveling at the endurance of the Jewish people. This same question was pondered by Samuel Clemens, more commonly known by his pen name of Mark Twain. In 1899, Twain wrote an essay called Concerning the Jews, and stated:

“The Egyptian, the Babylonian, and the Persian rose, filled the planet with sound and splendor, then faded to dream-stuff and passed away; the Greek and the Roman followed, and made a vast noise, and they are gone; other peoples have sprung up and held their torch high for a time, but it burned out, and they sit in twilight now, or have vanished. The Jew saw them all, beat them all, and is now what he always was, exhibiting no decadence, no infirmities of age, no weakening of his parts, no slowing of his energies, no dulling of his alert and aggressive mind. All things are mortal but the Jew; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?”

I have my own thoughts and theories as to what that “secret immortality” consists of. In short, I believe in the miracle of the Jewish people. I believe in the power of the Jewish neshamah, or soul. I believe in an unbroken chain of generations between myself, Abraham and Sarah, and all future descendants after me. And I believe in the providential guidance of the Almighty Who has promised that the Jewish people will survive indefinitely.

Sometimes I think about what Adolph Hitler (yamach sh’mo, may his name be erased) and the Nazis wanted to accomplish. They sought for the complete eradication of not just an entire people, but also of a religion, a culture, and even a set of ideas that are profoundly “Jewish.” And while their greatest damage was done by murdering over six million Jews, that wasn’t the only harm they inflicted. In true “Amalek” fashion, they “cooled off” many of the Jewish people. Even after the war, many Jews had no interest in maintaining their Jewish identity. Being Jewish became a hardship and a burden in their minds, and even a danger. So many Jews, including my grandmother, shed their Jewish identity, vainly believing that they could abandon it in the ashes of destruction scattered throughout the European continent. This more subtle attack was yet another strategy implemented by the Nazis. If they couldn’t destroy our bodies, then at least they would destroy our souls.

But I believe in the power of the Jewish soul. I believe that, one way or another, the Jewish people prevail over every obstacle, with the help of the Almighty. And as Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Memorial Day approaches, I like to do at least one extra mitzvah, or good deed. I like to do something extra that is distinctly “Jewish,” religiously or culturally. Because when I, as the granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor who had her spirit completely broken, openly embrace my Jewish heritage and use my Judaism to make a positive impact on those around me, I have a unique opportunity to proudly and defiantly declare to Hitler and the Nazis, “You lost. I won.”

This Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Memorial Day, I invite you to join me in these acts of kindness and Jewish religious traditions and cultural practices, and help me in declaring to the Nazis and all of our enemies throughout the millenia, “We won.”