(4-5 Minute Read)

Numbers 16:1-18:32

Korach and his band of mutinous Levites and other rebels, including Datan and Aviram, define the parasha, or Torah portion, of the same name. Korach and his supporters approached Moses and Aaron, accusing them of having too much control and authority over the Jewish people. Together with two hundred and fifty other Israelites, many of them being reputed community leaders, Korach led a short-lived revolution against the Almighty’s appointed leadership. The Most High was furious, and Moses begged Him not to destroy the entire congregation of Israel. Ultimately, after a final warning to the Jewish people to separate themselves from Korach and his followers, the earth “swallowed” the entire rebellious band and all of their belongings, apparently with some kind of miraculous, massive sinkhole, or something similar. The following day, the Israelites audaciously complained to Moses and Aaron that they had “unjustifiably” killed Korach and his band. In rage, the Master of the Universe released a plague on the congregation, and well over fourteen thousand persons died, besides the original destruction of Korach and his rebels. Finally, at the Almighty’s instruction, the chieftains of each tribe, including Aaron of Levi, were to place their rods before the Ark of the Covenant in the Mishkan, or Tabernacle. Whichever rod sprouted and budded indicated which tribal leader the Most High had chosen. As could be expected, the rod of Aaron sprouted with almond blossoms, and was placed with the Ark of the Covenant for a memorial for all time. The Holy One, Blessed Be He, further discussed the role, authority, and privileges of Aaron and the ongoing Levitical priesthood relating to offerings and tithes.

Interestingly enough, in the previous Torah portion, Shelakh Lekha, we read about the Jewish people being unable to shift out of a technical, direct mode of leadership. In other words, they wanted to robotically follow instructions, even from an oppressor. They were unable or unwilling to accept the “mentorship” of the Holy One, Blessed Be He, as well as Moses and Aaron in order to become their own Torah-based leaders. However, in this parasha, or Torah portion, we see the opposite trend. Korach and his rebels now insisted that Moses and Aaron were too much like dictators; rather, they claimed that they were all leaders, spiritual and otherwise. So much so, in fact, that they even accused Moses and Aaron of being tyrannical failures.

One aspect that is so fascinating about the Korach rebellion is how senseless and illogical it seems from our perspective as observers. The people of Israel were slaves in Egypt. Then the Almighty chartered Moses and Aaron to lead the Jewish people to freedom. In that process, the Most High performed great miracles, many of them connected with Moses and Aaron, such as the splitting of the sea and the provision of manna, quail, water, etc. Most pertinently, the entire community of Israel experienced the Holy One, Blessed Be He, at Mount Sinai. They even begged Moses to ascend the mountain and to speak to the Almighty on their behalf. So on what basis could anyone in the congregation of Israel possibly believe that Moses and Aaron were “unauthorized” leaders or even “tyrannical”? In fact, Korach and his band were so adamant in their claims, that they even agreed to a Levitical ceremony involving their fire pans to allow the Almighty to declare who was the true, Divinely-appointed leadership. This is especially noteworthy since Nadav and Avihu already died through an improper usage of their fire pans. And after the destruction of Korach, the Israelites still couldn’t accept Moses and Aaron as authoritative, and the Master of the Universe had to perform yet another miracle to prove again that Moses and especially Aaron were the authoritative spiritual leaders.

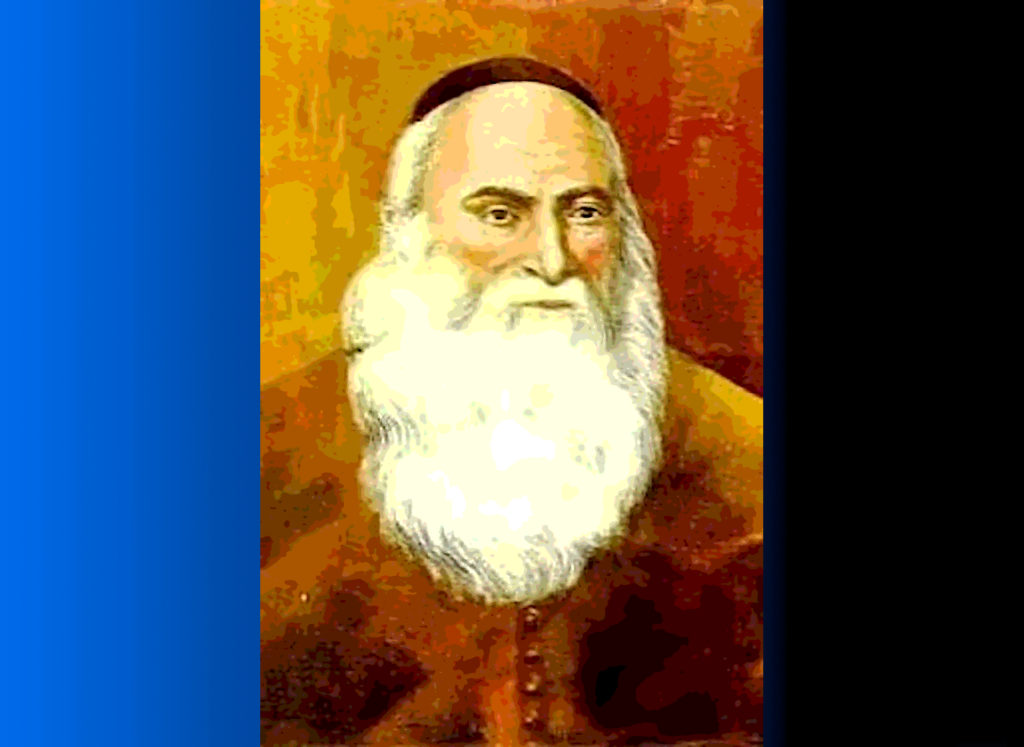

There are a variety of opinions on the matter. The Chassidic school of Pshyscha, for instance, postulated that Korach was overzealous spiritually, and it was arrogance rather than humility than led him to rebel. The great Sephardi commentator Rabbi Don Yitzhak Abravanel takes a much different approach. In a word, he presents the idea that the rebellion of Korach was a continuation of the mutinous unrest of the twelve spies and in some ways even the slanderous discontent of Miriam. Korach was jealous of Moses’ position of leadership, and he wanted to usurp it from him. Rabbi Abravanel further theorizes that there were several main aspects of the rebellion. First, Korach declared that since Moses of the tribe of Levi and the family of Amram had become a “king-like” executive leader, then the spiritual leadership should go elsewhere, and not to his brother, Aaron. Following that (improper) logic, Korach would have been next in line according to the Levitical bloodlines. The leaders of the tribe of Reuben, of which the notorious Datan and Aviram were an integral part, began to complain that they had no positions of leadership, spiritual or political. Jacob the patriarch had selected Judah to be the ruling tribe. And later the Almighty had chosen the tribe of Levi in place of the firstborns preserved during Pesach, or Passover, largely due to their dedication to the commandments of Torah during the infamous golden calf incident. Rabbi Abravanel likewise opines that the first born sons of the congregation of Israel were complaining that the tribe of Levi as a whole (which included Moses and Aaron) had replaced them in their spiritual leadership roles. Rabbi Abravanel opines that the first word of this Torah portion, “yikach,” or “he took,” references this idea that Korach unified three or more seemingly disjointed components of malcontent and molded them together into a single rebellion under himself. While many of these complaints were actually contradictory to one another, the rebels could all agree on one thing: they hated Moses and Aaron and wanted to get rid of him.

As far as why Korach and his rebels would agree to the fire pan ceremony that would enable the Most High to declare whom He had chosen, the motivations are less clear. One idea is that Korach felt that he could make enough technical and legal (albeit erroneous) arguments to establish his usurpation movement, even with the Almighty Himself. Another theory relates to the idea that perhaps Korach felt that his two hundred and fifty followers would “outnumber” and “outweigh” the two leaders, Moses and Aaron. It is also possible that Korach and his followers adopted a more “pagan” spiritual philosophy. As we see in the showdown between Elijah and the false prophets of Baal in Melekhim Bet (II Kings) 18, the pagan priests of Baal felt that their idolatrous false god could be “energized” by their shouts and blood offerings, or that they could manipulate their phony deity like “magic.” In contrast, the Torah makes it very clear that the Almighty is not ever manipulated by humanity; He is omnipotent and functions completely independent of human influence. Thus, understanding the premise of Abravanel as well as the greater context of the Torah and Tanakh, it is possible that either Korach arrogantly thought that the alleged “spiritual potency” of his band would outperform Moses and Aaron. Or, appealing to the same Israelites who had created and worshiped the golden calf, Korach adopted a more pagan methodology of trying to manipulate the Most High like “magic.” [Spoiler alert: it didn’t end well for Korach and his band.]

Perhaps the greatest lesson to be taken from the rebellion of Korach is the need for Jews to operate within the structure mandated by the Holy One, Blessed Be He, in the Torah. While Judaism is designed for its adherents to be adaptive leaders according to the Almighty’s commandments, part of that self-leadership involves maintaining and respecting the established authority structures of the Torah. Just as Judaism cannot function with authoritarian spiritual dictators, it also cannot function in a state of anarchy. A balance is required in which the Jewish community operates both independently but also in deference to the Torah-based leadership and guidelines.

As a final thought, another interesting note about this Torah portion is the “epilogue” to the Korach rebellion. The Torah tells us in B’Midbar (Numbers) 16:19-27 that the Almighty through Moses and Aaron ordered those family members or friends who were not an active part of Korach’s mutiny to separate themselves from the rebels and their dwellings. Thus, the innocent friends and family of the rebels were saved. Accordingly, we read later in the Torah and Tanakh that the sons of Korach did not die. Instead, they became loyal kohenim, or Levitical priests, and even wrote numerous tehillim, or psalms. Elsewhere in the Torah the Most High commanded us in Devarim (Deuteronomy) 24:16:

“The fathers shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the fathers; every man shall be put to death for his own sin.”

In other words, we see that the Master of the Universe followed His own mitzvah, so to speak. In so doing, the lives of innocent children were preserved, and key Jewish spiritual leaders and musicians continued to serve the Almighty and provide us with both Levitical service as well as tehillim, or psalms, of praise. Ironically, Korach rebelled against the Most High and the Torah in an effort to receive heightened positions of leadership. In contrast, his descendants aligned themselves with the Almighty and the Torah, and they have been established in a place of perpetual honor and respect.

May the Holy One, Blessed Be He, grant us all to operate both independently and also harmoniously and deferentially within the guidelines and authority structures provided by the Torah. And may we always strive to adhere to the principle of individual accountability that removed problematic rebellion from the Jewish community but also enabled the righteous descendants of Korach to reach their highest potentials of spiritual leadership.